This page provides the documentation for work presented at KA&S in June 2022.

Introduction

The tubular handled mug is an unusual vessel shape produced throughout much of Scandinavia and the adjacent parts of northern Germany and Poland over a period of several centuries in the Roman Iron Age (0-400 CE) and Migration Era (400-550 CE). They have a hollow handle that allows liquid to flow through the tube to an opening at the top.

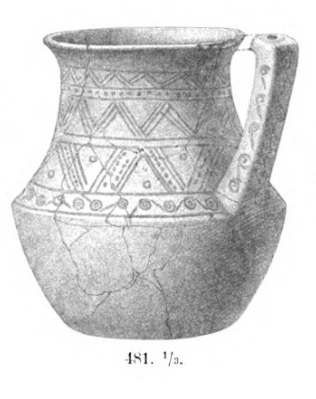

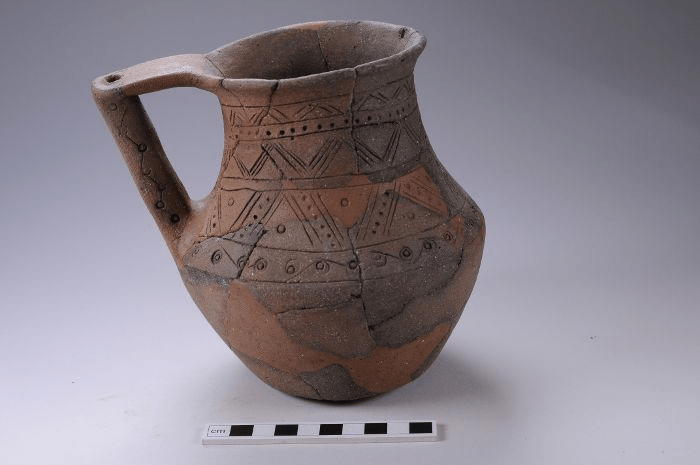

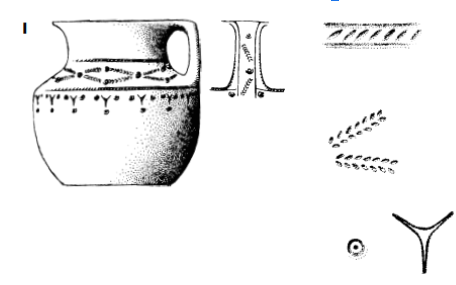

Although styles changed slightly over time and in different regions, the vessels all share the same general shape with a large belly, narrower neck, and an everted (turned outward) rim. Those from eastern Scandinavia have a distinctive form with a sharp bend between the upper and lower halves, known as a “carination.” The handle meets the pot directly on the carination. They are decorated with stamped and incised patterns. The upper half of the vessel is always decorated, and the lower portion and handle frequently are as well .

Gotland has the densest distribution of these vessels, which first appear in the 1st/2nd centuries CE and reach the height of their popularity in the late Roman Iron Age and Migration Era (3rd-5th centuries CE), persisting locally into the Vendel Period (Eriksson 2016, p.64-65). This particular style serves as the main influence for the work presented today. The images below show examples from the Historiska Museet in Stockholm, Sweden and two publications (scroll down or jump to the bibliography).

Since the 1950s, scholars have proposed various hypotheses regarding the intended function of the curious tubular handle–some suggest that the vessels were puzzle cups, lamps, or brewing pots (Erikson 2016). Another theorized that they were a northern European adaptation or imitation of Roman libation vessels used to pour liquid into a strainer (Hoftun 1998).

But how were these vessels made and how might they have functioned? The goal of this project was not to produce a perfect replica of a specific vessel, but rather a two-fold examination of process and purpose:

- experiment with methods of forming the handles to gain insight into how the mugs were assembled

- test out the replicas to evaluate the validity of the various hypothetical functions.

The pieces on display are proof of concept, and the results of the experimentation are documented here.

Background

What do we actually know about these vessels? Distributed widely throughout Scandinavia (see map below), many were found in burials, but others were excavated in settlements and inside houses and alongside other drinking utensils that show a correlation between ceremonial halls and ritual consumption (Eriksson 2016, p.61). While it is impossible to assign a clear value relative to other goods at the time, it is certainly a vessel type of a higher status than the more utilitarian wares that were undecorated and of coarser fabric. From a manufacturing standpoint, it is certainly one of the more complex ceramic forms found in Scandinavian graves during this general period.

Thomas Eriksson’s 2016 study found that among 36 pots complete enough to reconstruct, the volume ranged from less than half a liter to nearly 2.5 liters, and he theorized that smaller ones may have been for personal use while larger versions were serving vessels or used for communal drinking. Sizes generally increase along with the richness of the grave; this may imply a correlation between wealth and expected generosity, if those with greater means would have larger quantities of beverages to share (Eriksson 2016, p.66). There is also no correlation between the generic vessel type and any one particular demographic–examples appear in graves with men, women, and children, although Eriksson notes that the largest ones were generally found in very rich graves with multiple weapons (and thus assigned as masculine).

In his study, Eriksson puts forth an intriguing theory as to the significance of the tubular handle. He suggests that the vessels were used for mead, and that the hollow handle references the Germanic myth in which Odin steals the mead of poetry from the three cauldrons in the giant Suttung’s cave. The story is summarized in the Skaldskaparmal (see the excerpt here); in an effort to outwit Suttung, a disguised Odin enlists the giant Baugi to use an auger to drill a hole through the mountain and into the back of the cave. When the hole is bored, Odin transforms himself into a snake and disappears into the borehole, enters the cave, and drinks the mead. He then transforms again into an eagle, escapes from the cave, and regurgitates the mead into containers in Asgard; all who drank of it would become skilled poets (Faulkes, trans. 1987, p.62-64). In Eriksson’s analysis, the hollow handle of the mug symbolizes the auger hole, allowing the drinker to symbolically reenact the legend and “steal” the mead through a long narrow opening.

Construction and Use: Trial and error

To try to answer the questions I posed, I made four mugs that represent the small end of the size spectrum, at approximately 0.3 liters in capacity and roughly 10cm diameter at the shoulder (two have been rehomed for beta testing, two are presented here today). The following two sections address the possible methods of forming and attaching the handle and potential functions for this feature as part of beverage consumption.

Handle Formation

I tried out three methods for forming and attaching the handles to try to determine which one produced results that best matched the surviving examples:

- Bore out a solid handle after attachment

This was immediately discarded as a possibility. The slight curvature present in most examples makes this difficult or impossible, although this would be less of a concern on early examples with a straight handle. It is also much easier to form a tube around a stick or dowel rather than trying to pierce a solid cylinder.

- Form a curved handle and attach

A second attempt included the use of a slightly curved stick, reed, and pipe cleaner to see if this would work to allow a hollow handle to dry partway in its final curvature prior to attachment. This did not work well either. The form needs to be rigid enough to allow the clay to be shaped around it (the reed and pipe cleaner both failed), but because the handle curve is not a perfect radius, it was impossible to remove a curved stick without mangling the handle.

- Pull a straight handle around a rod; curve during the join process (see Figure 10)

This seemed to work the best; I was able to form a rough, thick tube around a straight stick and pull the middle portion of the handle, leaving some excess clay thickness at the upper portion and the tip of the stick protruding from the lower end. After boring a hole in the wall of the pot, the tip of the stick is inserted in the hole and the lower join is made, smoothing the excess clay downward from the handle onto the lower half of the vessel . The stick is then removed and the handle is bent upwards to form the desired curve. At the spot parallel to the upper rim of the pot, I cut halfway through the handle and bend it at a 90-degree angle to meet the rim, trimming it to length and slicing off the upper half of the tube. This then gets flattened and smoothed out, joined to the rim, and cleaned up a bit.

Winner: This created an appearance closest to the Stora och Lilla Ihre and Hästnäs examples; the handle is thicker at the top and tapers slightly towards the bottom, where material has been moved away during the pulling process. This is also more efficient than trying to guesstimate a handle shape with a set height and angle that is then attached after it is already formed most of the way–instead, everything is cut to length as I go. By joining the bottom of the handle first, I also have better access to be able to smooth and tidy up the joint before the rest of the handle is in the way.

Left: making the lower join with the stick in place. Right: cutting handle to height and opening out to form the portion that joins the rim.

Functional Testing

Once the mugs were fired, I began to play around with potential functions for the hollow handle. I arrived at the conclusion that three broad categories were possible: I call them “Pour,” “Ignore,” and “Simulate Lore.”

Pour

One thing became abundantly clear the moment the first mug was complete – as I had surmised, the design of the tubular handle defies all potterly wisdom about how to make a functional spout. The proportions of the handle do not allow for substantial tapering of the tube, which is necessary to increase liquid pressure during the pouring action and create a good, steady flow without dribbling. Similarly, although some of the earlier examples have a more defined angle to the handle’s upper edge and a flatter surface, this feature becomes more rounded in later examples (compare Figures 5 and 7). The angle of the spout opening relative to the plane of the vessel top also affects pouring, and the later examples with a more rounded handle-top do not cut the flow off cleanly. As a pouring jug, this vessel type is not well designed and would dribble–as was demonstrated in the first round of testing–to the point of near uselessness, making Hoftun’s theory that it was used to pour ritual libations into a second “sprinkler” vessel with a perforated base seem improbable.

I should note that my initial group of test pieces were all close to the small end of the size spectrum (around half a liter). Several months later, I made a larger one that holds just over a liter. I found that the pouring action was not as bad, possibly due to the greater pressure produced by twice as much liquid attempting to escape from more or less the same diameter exit hole, but it was still not a very good serving vessel.

Ignore

With a pour-spout function now seeming far less likely, I tried out some other potential uses that treat the hollow handle as an aesthetic feature not integral to beverage consumption. While drinking from it just like any other mug, I found that as long as the handle is between 9 o’clock and 3 o’clock relative to the user’s face, the liquid does not flow out the tube. If it was intended as a puzzle cup, it is not a very difficult puzzle, and once solved, the solution is universally applicable across all the various examples. Given the wide geographic distribution of such vessels, it is also less likely to have been a complete novelty to a guest in someone’s hall. It is also very simple to close off the hole at the top of the handle with the thumb while drinking. However, these two use cases treat the tubular handle as an obstacle at worst and superfluous at best, which seems antithetical to the amount of effort required to make it.

The single handle also becomes increasingly awkward as the size of the vessel increases; the weight of over 1.5 liters of liquid, combined with the weight of the pot itself, makes for a fairly unwieldy affair to try to use as a large flagon. And unlike those of the oversized beer steins some modern drinkers may be familiar with, the Gotlandic handles themselves do not accommodate an adult’s entire hand. The handle loops on the larger examples tend to be at most 5-6 cm high and 3-4 cm across, which is a diameter sufficient for two or perhaps three adult-sized fingers. This type of handle is perfectly sufficient for use when using the handle to tilt the vessel along a parallel axis, as when pouring from a large jug while supporting the vessel with a second hand. For perpendicular tilt, not so much; maneuvering a full one like a modern mug without the use of a full-fist grip is not a particularly ergonomic experience. It is worth noting other examples of larger, handled communal drinking vessels from other time periods and cultures frequently have a handle on each side (for example, many Bronze Age vessels from the Aegean, or the cogs used in Orkney today).

Simulate Lore

If Eriksson’s hypothesis is correct, the act of drinking directly from the opening atop the handle would connect the user directly to the central mead-myth, as they symbolically reenact Odin’s theft of the mead of poetry through a narrow shaft bored into rock. In this scenario, I treated the handle/spout like a drinking straw. This works remarkably well. When the vessel is mostly full, and as long as the liquid level is above the pot’s shoulder, it functions beautifully as a sippy cup even when held completely vertically. The attachment point at the sharply-defined shoulder also ensures that as the liquid level diminishes, tipping the vessel towards the drinker continues to funnel all the liquid to the bottom of the spout/handle. In short, it works spectacularly when used this way, and is a tidy way to consume a beverage from either a personal mug or a giant communal bucket of mead.

Materials, Tools, and Decoration:

Vessel construction

Portions of Scandinavia had begun to use the potter’s wheel in the Roman Iron Age, although this appears to be dependent on the degree to which there was a demand for highly-specialized ceramic production in a given area (Collis 1984, p.15). Early examples of tubular handled mugs from the 2nd or early 3rd century CE are clearly hand-built, displaying obvious irregularities. Many later examples from the Migration Era onward (4th-6th centuries CE) are far more regular, and some fragments in the Historiska Museet in Stockholm’s online database show horizontal striations that suggest that they could have been produced on either a “fast” wheel or at the very least a tournette or “slow wheel”–in either case, the potter’s hands or tools are held stationary while the vessel is rotated past them, producing an even form that may retain horizontal drag marks. Without any decisive evidence for the exact technology used to produce the Gotlandic exemplars, I made my mug bodies on a kick wheel at a fairly low RPM. I attempted to keep the walls of the vessel within the range of thicknesses documented (not to exceed 5mm), so that even if the forming method is not correct, it will not inadvertently compromise the characteristics of the vessel that are crucial to understanding its performance.

Tools

I used a combination of cattle bones and seashells as rib tools to shape the forms, and then decorated it with stamping dies I carved from antler and bone. The stamping dies replicate the motifs found on several examples shown in the images below, and the use of antler dies is supported by archaeological finds from multiple locations in Europe dated to the Migration Era and Early Medieval period (von Hessen 1968). To read more about stamped pottery decoration and the use of antler stamping dies, take a look at my ongoing gigantic project here.

Clay body/Firing

Archaeological reports describe examples of tubular-handled vessels from Gotland as “thin, finely tempered, well-fired ware” (Rundkvist 2016, p.227); “reddish grey finely tempered ware, 3mm thick at the shoulder” (Rundkvist 2016, p.201); “Finely tempered terracotta ware, 4.5mm thick at shoulder” (Rundkvist 2016, p.211); and one enormous example is described as “finely tempered grey ware, 5mm thick at the shoulder” (Rundkvist 2016, p.198). A range of colors are thus demonstrable, likely the combination of natural clay color and firing conditions. Regarding the latter, the catalog entry for a Migration Era tubular handled mug from Hästnäs, Visby, Gotland (Svenska Historiska Museet, Inventory No.18913/V 3) notes that it is oxidation fired. By modern standards, each of these examples would likely be classified as earthenware, as kiln technology did not allow European users to approach stoneware temperatures until later–for example, sampling and analysis from a Roman-style updraft kiln from Belgium in use between 170 and 295 CE showed that the typical firing temperature was around 600 C (Spassov & Hus 2006). Another contemporary kiln from Bulgaria fired to 780°C and occasionally reached 860°C (Lesigyarski et al. 2020), a temperature range still well below the typical firing range of modern earthenware clays. Analysis of other Migration Era material from Norway found that 1000°C represented the likely upper end of the firing range (Engevik 2008), comparable to a low-average temperature for a modern earthenware.

A perfect replica of a Scandinavian tubular-handled vessel should therefore be earthenware, skillfully fired with wood in a clamp or an updraft kiln to achieve an even color, whether in an oxidation (as noted on the Hästnäs example) or reduction environment. I substituted a modern clay body (Continental Clay Mid-Range Oxidation) that is fairly finely tempered and within the general range of colors displayed by historical examples, but fires to 1240-1260°C (Cone 5/6 ). While I have not personally handled the originals, my hope is that the hand feel is similar. I do not have a readily accessible site for building a clamp or updraft kiln, although that is on the docket for later this summer on a different property, so these were fired in my electric kiln. The primary goal of this project was to understand the method of forming and attaching the handle–all of which happens while the piece is still wet/damp–and to test out the finished vessel to see how it performs in various use cases. Having worked with a variety of different earthenware and stoneware clay bodies, I do not believe that the clay properties vary so much that there would be a noticeably different forming and assembly process, and a more authentic firing method would not have yielded more information about the pot form and fabrication process.

Once fired, my vessels are less porous than the originals likely were, however, although burnishing/polishing or sealing with milk protein or wax (no information was available regarding trace residues on surviving examples) may have alleviated this in period. Regardless, I also tested the pouring capabilities while the vessels were still bisqueware (Cone 04, about 1060°C), at which point they were still extremely porous; compared to the pour tests once out of the second firing, I did not find that the hydraulic properties were strongly affected by differences in porosity and I think the “product testing” data is still valid. When pouring, they dribble miserably regardless of porosity and it is impossible to direct the flow accurately. Although the originals were unglazed, I applied a very thin matte clear glaze to the interior for the sake of food- and dishwasher-safety, and this is discreet enough that it does not compromise the period appearance too much. A side bonus is that by making them modernly food-safe/dishwasher-safe, I stand a higher likelihood of getting more people to use them and provide ongoing feedback about their performance and properties as drinking vessels since no one wants to put mead in something they can’t easily clean.

Conclusion

After quite a bit of trial and error, I have arrived at an assembly method that addresses the main “pain points” of this unusual handle type (maintaining/creating a curved tube, ease of access to the lower join). While I cannot be certain it is the historically correct method, it is the most straightforward way of doing it and of the various methods I attempted, also produces a handle that most closely matches the parameters of the originals. My experiments in drinking from the test vessels have also provided some insight on potential functions, and although it is impossible to say for certain that the handle was used to drink directly from the vessel, it is the function that the feature seems best suited for. When coupled with Eriksson’s theory regarding the mythological origin of the mead of poetry, it builds a compelling case for this particular use.

Sources:

Almgren, O. and Nerman, B. (1923). Die ältere Eisenzeit Gotlands, Stockholm. Kungl. Vitterhets- historie- och antikvitetsakad. Wahlström & Widstrand.

Collis, John. (1984). The European Iron Age. London: Routledge.

Engevik, Asbjørn. (2008). Bucket-shaped pots: Style, chronology and regional diversity in Norway in the late Roman and migration periods. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Eriksson, Thomas. (2016). Suttung’s Mead and Jugs with Tubular Handles in Sweden. Petterson, Paul Eklöv (ed.). BAR S2785: Prehistoric Pottery Across the Baltic. British Archaeological Reports, Ltd.

Hessen, Otto von. (1968). Die langobardische Keramik aus Italien. Wiesbaden: Steiner.

Hoftun, O. (1998). Kultisk keramikk i jernalderen. Fornvännen, 1998 (93.2), p.81–88.

Lesigyarski, D, Jordanova, N, Kostadinova-Avramova, M, Bozhinova, E. Clay source and firing temperatures of Roman ceramics: A case study from Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Geoarchaeology. 2020; 35: 287– 309. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21770

Rundkvist, Martin. (2003). Barshalder 1: A cemetery in Grötlingbo and Fide parishes, Gotland, Sweden, c. AD 1-1100; Excavations and finds 1826-1971. Stockholm Archaeological Reports 40. Department of Archaeology, University of Stockholm.

Spassov, Simo & Hus, Jozef. (2006). Estimating baking temperatures in a Roman pottery kiln by rock magnetic properties: Implications of thermochemical alteration on archaeointensity determinations. Geophysical Journal International. 167. 592 – 604. 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.03114.x.

Sturlusson, Snorri & Faulkes, Anthony (trans.). (1987). Edda. London [etc.: Dent]

Online database of the Historiska Museet, Stockholm, accessible at https://mis.historiska.se/mis/sok/sok.asp

“Then Bölverkr [Odin’s false name] got out an auger called Rati and instructed Baugi to bore a hole in the mountain, if the auger cut. He did so. Then Baugi said that the mountain was bored through, but Bölverkr blew into the auger-hole, and the bits flew back at him. Then he realized that Baugi was trying to cheat him, and told him to bore through the mountain. Baugi bored again; and when Bölverkr blew a second time, the bits flew inwards. Then Bölverkr turned himself into the form of a snake and crawled into the auger-hole, and Baugi stabbed after him with the auger and missed him. Bölverkr went to where [Suttung’s daughter] Gunnlöd was, and lay with her three nights; and then she let him drink three draughts of the mead. In the first draught he drank everything out of Ódrerir; and in the second out of Bodn; in the third out of Són; and then he had all the mead. Then he turned himself into the form of an eagle and flew as hard as he could.”

Excerpt from Skaldskaparmal (Faulkes trans.)

Note: Ódrerir, Bodn, and Són are the names of Suttung’s three mead cauldrons