Part I: Migration Period and Early Medieval Europe

This page provides an overview of the project. A portfolio of selected past work is here. You can also check out my project journal for blog posts with more detailed information on individual stamps and pots, musings on the process, and other periodic updates. Part II of the project focuses on Late Antiquity in the Roman provinces; click here to read more.

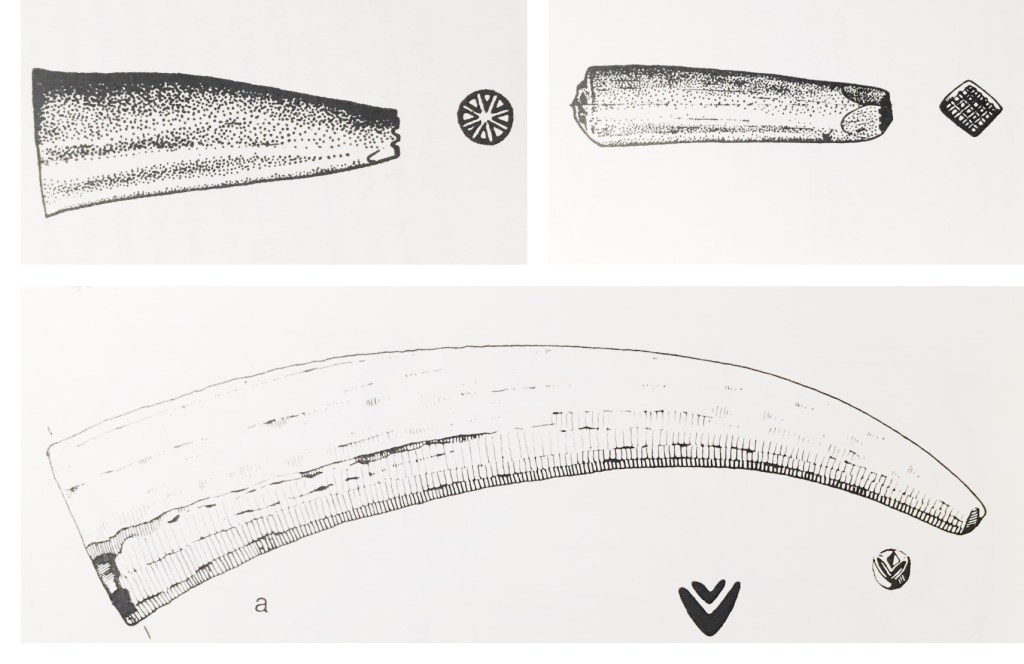

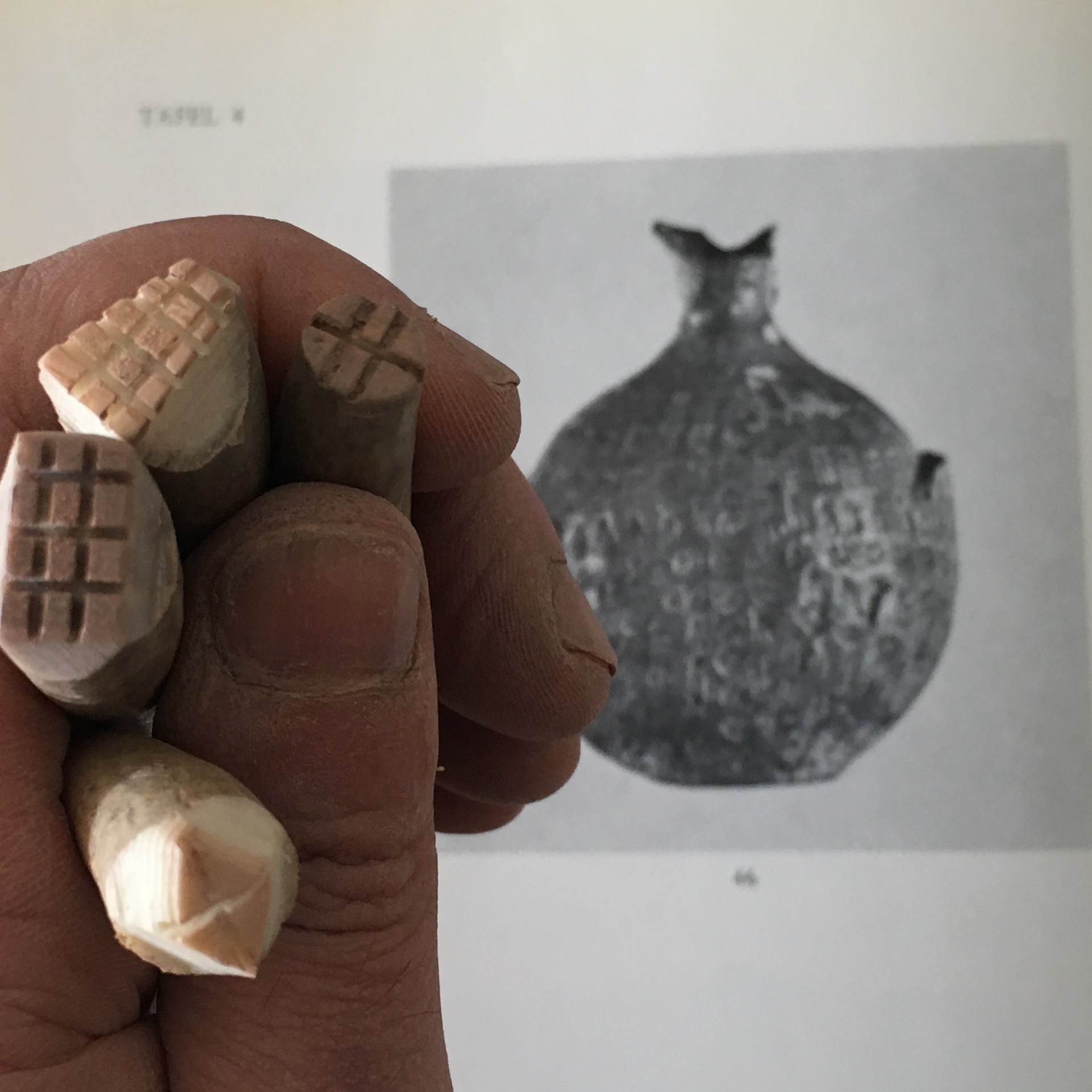

Since I started making Migration Era and early medieval pottery, I’ve been slowly building up a collection of stamping dies replicating the impressions that decorate a wide range of pots from Langobard, Frankish, Alemannic, Saxon, and Gotlandic contexts from the late 5th through 8th century CE. I carve the stamp dies out of antler tips, since this what many extant examples are made from – see illustration below, or take a look at these from West Stow and Medbourne in England. Four examples from West Stow, England have been identified as red deer antler tine, and at least three other antler dies were found in East Anglia as well (Briscoe 1981). Stamp dies from this period made from lead or copper alloy have also been found in England, although it is unknown whether some copper alloy ones like this one were used for leatherwork rather than pottery.

Stamped decoration on pottery has a long history – many Iron Age European cultures produced ceramics decorated with individual stamps, and this continued well into the Middle Ages. Some of these designs persisted for many centuries; this 7th c. BCE Etruscan pot uses a rosette not unlike ones that adorned pots made in the 6th and 7th c. CE. Some motifs were extremely widespread, while others seem to be more regionally specific. I have yet to run across a scholarly publication that provides a comprehensive chronological and geographic overview of pottery stamps across both continental Europe and Britain, and I am leery of making any generalizations about certain stamp motifs being associated with any particular culture or group, so I’ll present them here based primarily on geography – the modern-day location of the pot bearing the stamp – although some stamps clearly have enjoyed popularity across many regions. If I am feeling industrious, I may eventually map the locations of various stamps to see what trends emerge, but that is a much longer-range project.

Tools

Most of the designs can be carved using fairly simple tools such as saws, knives, small augers or drills, rasps, and handheld ring-and-dot augers. All of these tools were typically used for antler- or bone-working during this broad time period (check this source out for more information; a dated list of tool finds can be found on page 23) and have been documented at various locations in northern Europe between the 4th and 9th centuries CE (see Wilson, 1976 and MacGregor, 2003).

While some of the simpler designs could be made by anyone with a sharp knife, the others require the use of the same types of tools that were used to make and decorate bone combs and other items (the image below shows my toolkit). It is possible that potters may have made their own stamps, especially some of the simpler ones, but more complex designs could also have been produced by boneworking specialists.

Basic shaping is done using a knife or saw; I made a small string-tensioned bow saw that is a simplified version of a 2nd century CE example found in the Netherlands (in the wreck of a Roman river boat). Mine is fitted with a modern hacksaw blade that creates a cut just over 1mm wide, comparable to the tooth spacing width of fine-toothed Migration Period combs (see Ashby, 2006; Ashby, 2007). My knives are hand forged by others, as is the square awl I use for certain details. I have produced several of my own ring-and-dot tools using old screwdrivers and nails, and purchased one, along with the bow drill that I use to bore holes, from Daegrad Tools in Sheffield, England. I made my makeshift graver from a square cut iron nail.

General Forms

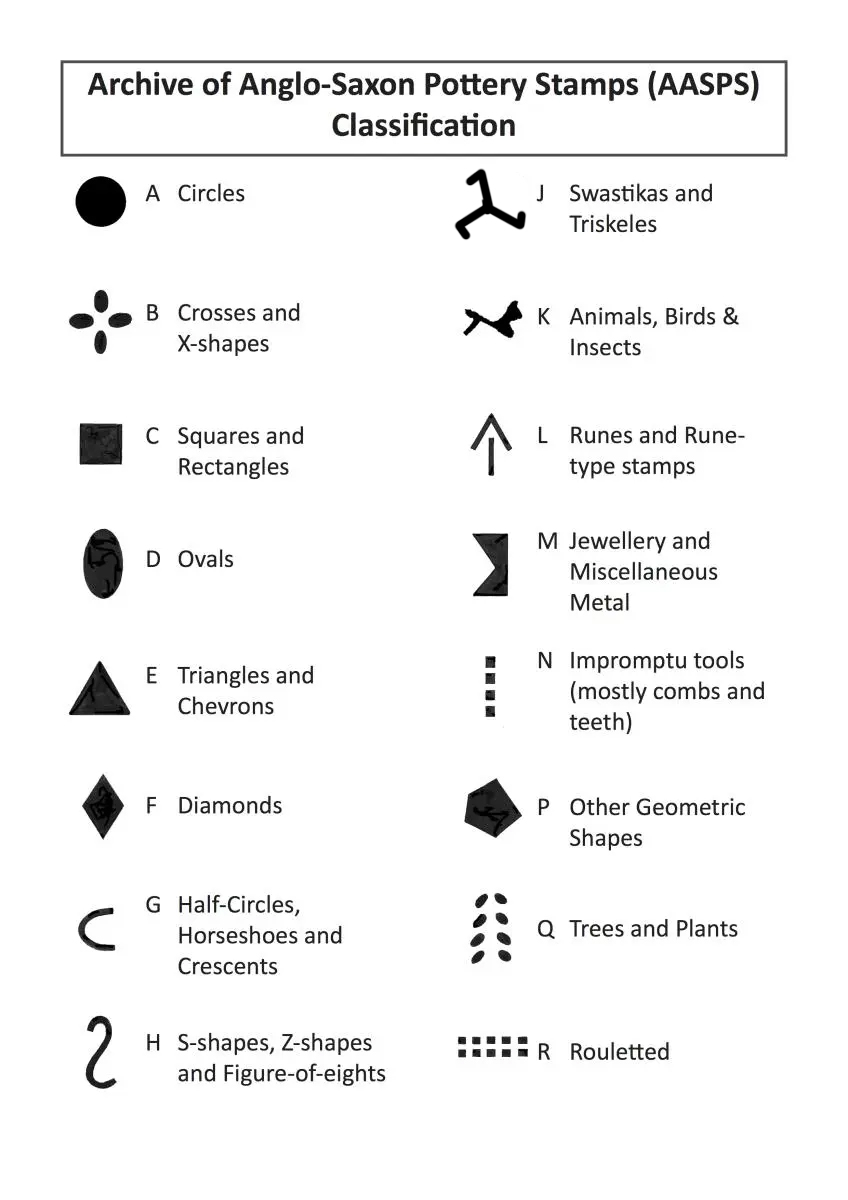

For the most part, stamps from this time period and these cultural contexts fit into a handful of broad categories. The classification system developed for the Archive of Anglian & Saxon Pottery Stamps (AASPS) is useful in grouping pottery stamps from many other areas with similar pottery traditions, including continental Saxon, Frankish, Langobardic, and Gotlandic wares. Published by Teresa Briscoe in 1981, the AASPS system now defines 17 overarching categories based on the overall outline of the stamp, including forms like circles, crosses, squares/rectangles, diamonds, half-circles/horseshoes, and leaves. Many of these shapes are subdivided with different patterns of intersecting lines as well – for example, circular stamps can be bored out to make simple hollow circles, or cut with radial lines like an asterisk to form a “rosette,” or cut into a grid. The image below shows a couple of test panels with stamps of many different types alongside the general classification system developed for the AASPS; scroll down for more details on individual stamps and their sources.

As I began to replicate the stamps seen on pots in various archaeological reports and photographs from museum collections, it became clear that the tools and materials lend themselves well to certain designs, and none of the motifs I’ve copied required me to fight the materials or use anything more than common sense to figure out the order of 12 or fewer (usually straight-line) cuts. Some aspects of stamps indicate both practical and aesthetic considerations; beveling the edge of a stamp creates a rounded impression rather than a sharp edge around the perimeter, but also allows the maker to easily create a straight-line cut that does not completely bisect the stamp face – the tool is held at an angle, so there is no need to worry about stopping the cut from going too far – see diagram below. If the face is not beveled, the raised ridges would be much taller closer to the edge of the impression and would be less durable.

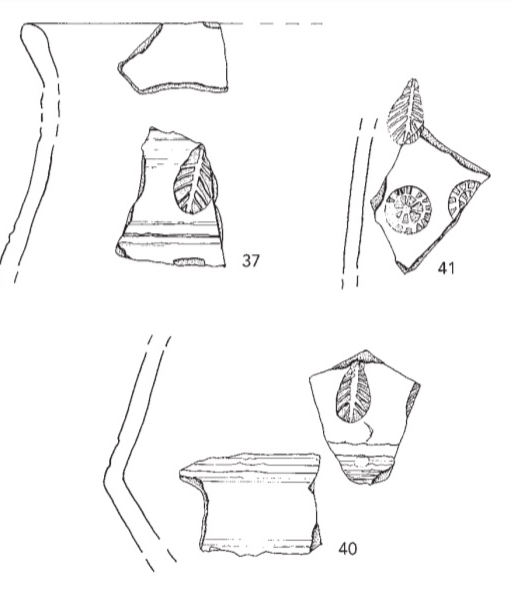

In some cases, the materials themselves may have dictated the shape or at least inspired the maker – for example, the natural cross-section of some antler tips creates the leaf-shaped form seen in these stamps below without any additional work besides carving the lines on the face of the stamp itself. Antler also has a more porous core, which lacks the smoothness and density necessary to hold a crisp carved edge; the hollowed center of many stamps eliminates this area.

Leaf-shape and rosette stamps based on a group of pots from Kaiseraugst, Switzerland (Marti, pl. 69 & 70).

The gallery below shows 40 of the stamp dies I have produced so far, organized according to the AASPS classifications. While I provide a citation for each one in the captions, please note that this represents one instance of a stamp that may in fact appear on multiple pots or across a wide geographic range. Each group is also shown with a sample impression, and you can scroll down to see some examples of pots I’ve decorated with them as well. The bibliography at the bottom of this page contains the source publications I have cited throughout.

CIRCLES

Rosettes

These round stamps have radial lines cut across their faces. In some examples, the lines intersect, while others may only cut into the edge. Some examples have a hollow center – often this is bored out with a plain auger, but occasionally a ring-and-dot auger may have been used, adding one or more concentric rings, as on the far right.

CIRCLES & OVALS

Rings, crosses, and grids

The simple circle stamp at far left is a cross-section of antler with the center bored out with an auger. While mine is scaled from a Langobard example, this is a common motif in the part of Britain settled by Saxons, as is the cross second from left, and both of these appear in Vendel-Period Scandinavian pottery as well. The other circular and oval stamps are broken up with intersecting straight lines in crosses and grids.

CIRCLES

Ring-and-dot, complex crosses

Some round stamps are more complex; these can involve the ring-and-dot motifs common on many contemporary metal and bone artifacts, as well as more intricate patterns of perpendicular lines and dots.

TRIANGLES

Dotted and incised

Triangular stamps with one or more holes bored in the middle, such as those on the left, are virtually identical to those that appear on metalwork, Others incorporate more detailed patterns of incised lines.

TREES & PLANTS

Leaf-shaped

This broad classification (“Q” according to the AASPS system) includes many stylized leaf forms. The second from left appears on a Frankish pot found in the Netherlands, where it was used to form a T-shape described in the museum catalogue as a “Thor’s hammer.’ Leaf forms sometimes include a hollow ring at the top, as in the middle example found on a Langobard jug.

CROSSES & X-SHAPES

Cruciform

These cross-shaped stamps all begin as round sections of antler and four notches are gradually enlarged to form the arms of the cross. From there, additional lines and dots across the face of the die add detail. The notched cross at the far left is an extremely widespread motif in the 5th-7th centuries, appearing on pots from Italy, Britain, and Scandinavia.

DIAMONDS

Lattices and Grids

The diamond shape is often further subdivided by intersecting lines forming a grid, cross, or lattice pattern. The lattice diamond is common across many geographic regions during the early medieval period but was extremely popular in Langobardic areas.

RECTANGLES

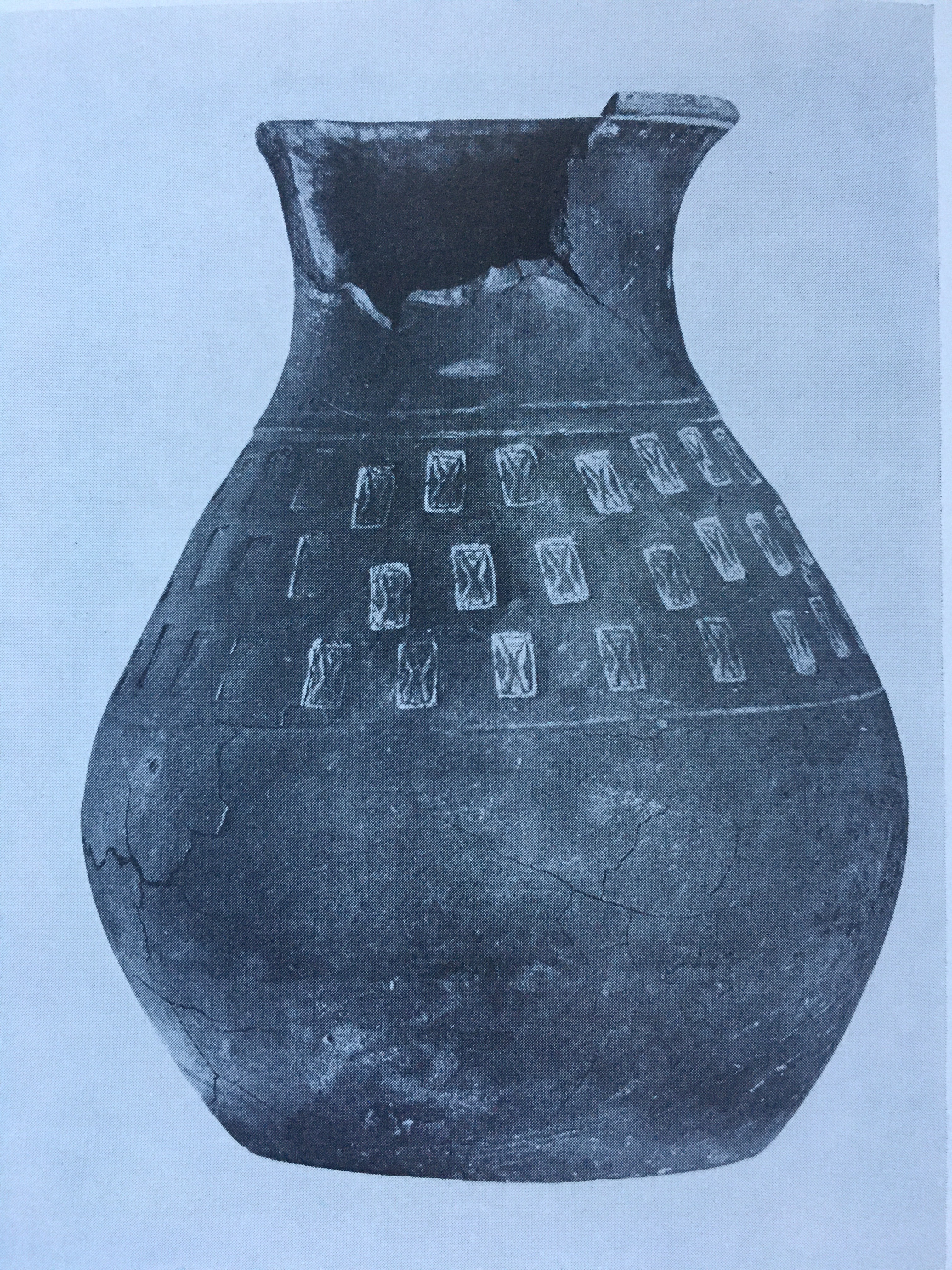

Grids and small squares

These rectangular shapes (second from left is a trapezoid, sorry) are subdivided by parallel and perpendicular lines to form rows of small squares. Some may have a single row, while others have multiple rows or may be separated by a wider strip of negative space, such as the stamp on the far right.

SEMI-CIRCULAR/SEMI-ELLIPTICAL

Half-circles, horseshoes, crescents

These forms consist of a circular or elliptical cross section with a portion cut away – typically less than half the area of the cross section – to form a horseshoe or U-shape. The face of the stamp may have a single hollow at the center or may have been cut with concentric circles. Note the removal of the porous core of the antler to create the hollow center on the rightmost example.

Fabrication

The first step in reproducing a historical stamp is to deduce the shape from the impression. In looking at a photograph, I have to rely on the way the stamp catches light (or dirt, sometimes) to understand which portions are positive or negative space and which parts of the impression are deepest. Some stamps have a flat face and make an impression of uniform depth, while others have a more rounded impression, indicating that the face of the stamp may be beveled. From there, I can determine the layout of the cuts and make them with a knife blade, saw, or file, and bore out the center if needed. While working, I like to test the impression using a gray kneadable eraser so that I can see the details and make minor adjustments before using it on clay. Once I am satisfied that it produces an impression that looks like the original example, I make some pots.

In the example shown, the T-shape on this Frankish pot from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden is made using the same stamp twice in a perpendicular arrangement. In looking at the shadow, I can see that the long central ridge sits lower in the impression than the short angled cuts, which seem to be a consistent height and end much closer to the surface. This indicates that the long edges of the stamp are likely beveled to slope away from the central ridge.

I started with the long central cut, beveled the edges away from it, and then made my side cuts. I tested the impression on a bit of kneadable eraser and made some minor adjustments until I was satisfied.

The final test looks pretty good to me, although when I tried out the T-shape, I decided I may want to shave the edges a bit narrower so that it looks more like the original exemplar I’m using.

Once that’s done, I made a pot with it. The original was stamped with four T-shaped decorations, evenly spaced around the outside on the upper half of the form. This shape is called “biconic” (knickwandtopf in German, knikpot in Dutch) and is extremely common in this period – the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden collection includes 150 biconic pots of various sizes and proportions were found in Rhenen, where the exemplar was excavated.

Here are a few other examples of stamps I’ve made based on some Langobard pottery; images of the originals are shown above the reconstructed stamps and their impressions:

In some cases, the pattern may involve a more complex arrangement of stamps. In this example of a late 6th-century Frankish pot from the Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, three stamps make up the design: a small 3×7 grid rectangle, a “W” shape, and a semi-circular stamp with narrow teeth. The semicircular stamp is used in an alternating position to create the undulating line, and if you look closely in the museum database photos (visit link above for high-res), you can see the areas of where the ends of the stamp impressions overlap in a few places on the pot (indicated by arrows). Below is a test impression as I was working on the three stamps needed to replicate this pot. For the final version, I will need a wider piece of antler for the semicircular stamp, but the other two are pretty close to the original scale.

Drawing of the pot is from the original article publishing the find (scroll to bottom of this page for bibliography).

My pottery blog has writeups of several other projects where I’ve reconstructed groups of stamp dies based on a specific pot. You can check out a group of five that I made for a replica of an Anglian urn here.

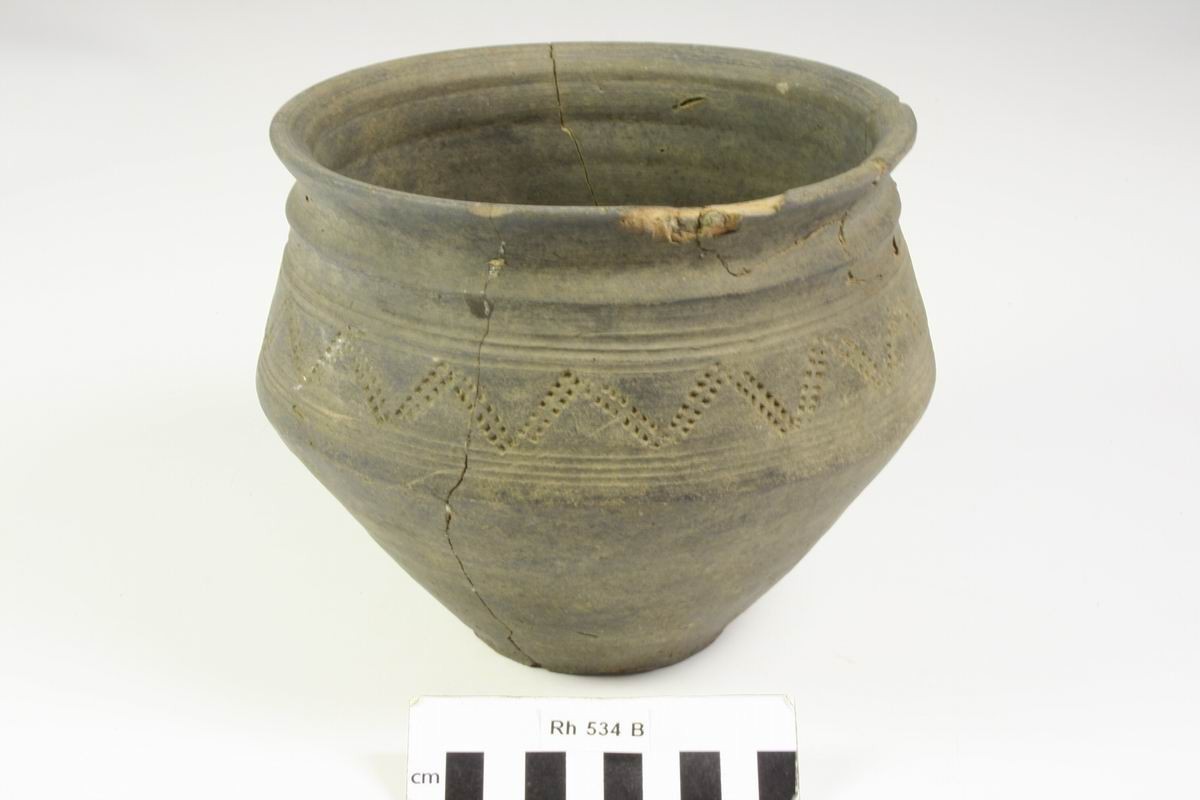

Gallery

The images below are some more historical examples of Saxon, Langobardic, and Frankish pots and show how the individual stamps could be arranged to make different patterns – either using a single stamp or in bands composed with multiple stamps. Unless otherwise noted, images are from museum collections and are used here under the CC BY 4.0 license. Click any image for additional information.

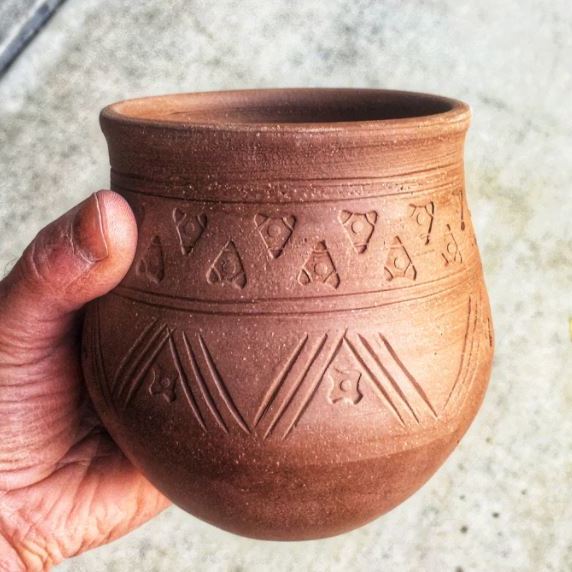

Here are some examples of my own pots, decorated with the stamp dies I’ve cut.

Sources:

In addition to the pottery collections of the British Museum and the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, the following publications are the ones cited in image captions and provided the sources for most of the stamps I’ve made.

Briscoe, Teresa. (1981). Anglo-Saxon pot stamps. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 2. Oxford: BAR British Series 92. 1-36.

Evison, Vera I. (1979). A corpus of wheel-thrown pottery in Anglo-Saxon graves. [London]: Royal Archaeological Institute.

Lamberti, Marina. (2014). LA CERAMICA LONGOBARDA IN ITALIA TRA VI E VII SECOLO. Thesis, University of Florence. 10.13140/RG.2.2.20181.22244.

Marti, Reto. (2000). Zwischen Römerzeit und Mittelalter: Forschungen zu frühmittelalterlichen Siedlungsgeschichte der Nordwestschweiz (4. – 10. Jahrhundert) [1] [1]. Liestal: Archäologie- und Kantonsmuseum Baselland.

Myres, J. N. L. (1977). A corpus of Anglo-Saxon pottery of the pagan period. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.

Niemeyer, Wilhelm. (1957). ‘Kleine Beitrage: Ein bemerkenswerter merowingischer Fund aus Niedervellmar bei Kassel’ in Zeitschrift für hessische Geschichte und Landeskunde 68. 209-212.

Rundkvist, Martin. (2003). Barshalder 1: A cemetery in Grötlingbo and Fide parishes, Gotland, Sweden, c. AD 1-1100; Excavations and finds 1826-1971. Stockholm Archaeological Reports 40. Department of Archaeology, University of Stockholm.

von Hessen, Otto. (1968). Die langobardische Keramik aus Italien. Wiesbaden: Steiner.

Wagner, Annette, Jaap Ypey, and Annemarieke Willemsen. (2011). Das Gräberfeld auf dem Donderberg bei Rhenen: Katalog. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Additional information on bone- and antler-working:

Ashby, S.P. (2006) Time, trade and identity: bone and antler combs in Northern Britain c.AD 700-1400. PhD thesis, University of York. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/14191/.

Ashby, S.P. (2007) “Bone and Antler Combs,” Datasheets of the Finds Research Group 40. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/75225/

MacGregor, A. (2003). Bone, antler, ivory & horn. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.

Wilson, D. M. (1976). Craft and Industry. The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England. London, Methuen.

Further reading for historical background:

Effros, B., & Moreira, I. (2020). The Oxford handbook of the Merovingian world. Oxford University Press.

Halsall, Guy (2008). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge University Press.

Jesch, J. (2003). The Scandinavians from the Vendel period to the tenth century: An ethnographic perspective. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press.

Wood, I. N., ed.. (1998). Franks and Alamanni in the Merovingian period: An ethnographic perspective. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.