Part II: Late Antiquity

Pannonian Slipped Ware: 1st-2nd c. CE

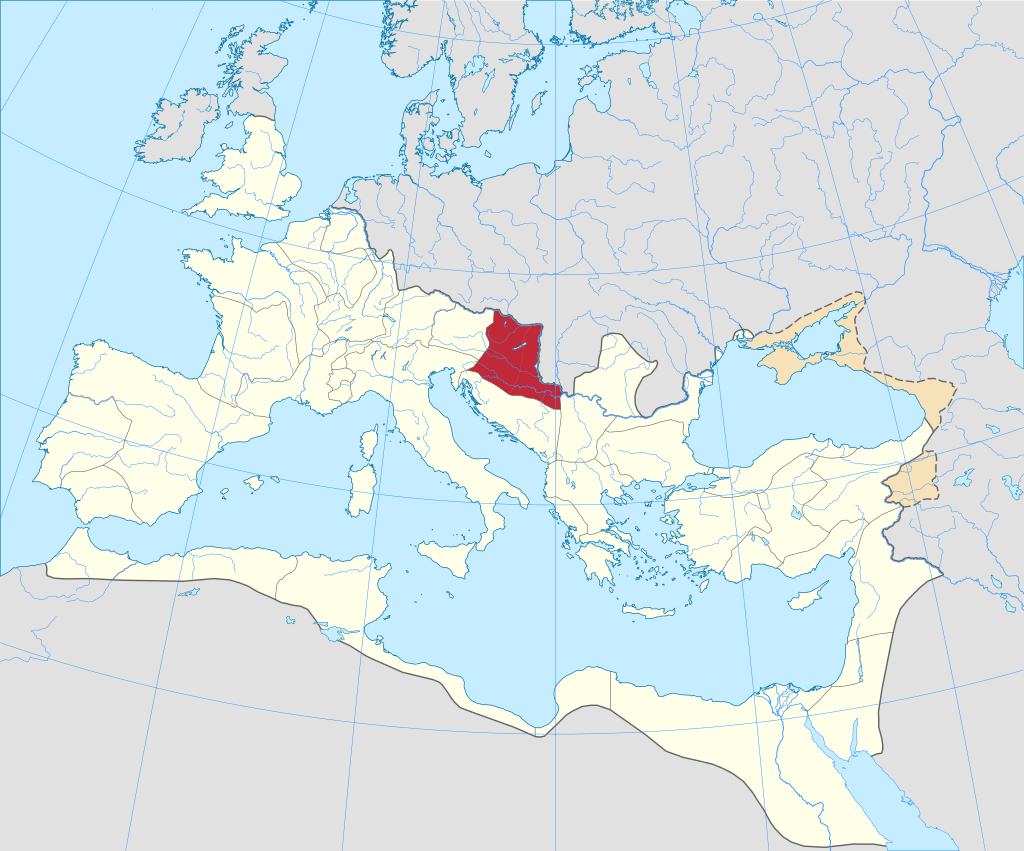

This project was begun in late 2022 and is an outgrowth of my previous work with northern European pottery stamping dies from the Migration Period and Merovingian/Vendel Period. This time around, I’m working on reconstructing a group of stamp dies based on pottery produced several centuries earlier in the Roman province of Pannonia, a portion of the Roman empire near the Danube River (today this area is part of Austria, Hungary, and the northern Balkans). Known as Pannonian Slipped Ware, it first appeared toward the end of the 1st century CE and continued into the early 4th century CE, and represents the fusion of Roman style with Pannonian tastes and tradition as local potters began to make wares inspired by Roman imported ceramics.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Most of the examples presented here are based on pots produced in workshops near the town on the Danube that the Romans called Aquincum, where the modern-day city of Budapest is located today. Aquincum was an important part of the Roman defenses along the frontier or limes, and by the beginning of the 2nd century CE, the 6,000-man Legio II Adiutrix was headquartered there. Excavations of the military and civilian settlements have yielded many examples of Pannonian Slipped Ware.

Although this project is focused on Pannonian Slipped Ware, a brief discussion of a different type of Roman pottery known as Samian Ware is important to understand the context. This type of pottery served as the inspiration for the Pannonian wares, but the manufacturing methods are different–Pannonian Slipped Ware uses a direct-stamping method to imitate the look of mold-made imports.

Import and Inspiration: Samian Ware

The Romans’ conquest of the Eravisci (the local Celtic or Pannonian people) and subsequent occupation of this area meant that trade goods from elsewhere in the empire were accessible and desirable, including Samian ware, a glossy reddish pottery often decorated with elaborate raised designs of plants, human and animal figures, and geometric patterns. Samian ware was mass-produced in Gaul and exported in large quantities throughout the empire, giving rise to imitations in several provinces. In Pannonia, local potters began to imitate this type of pottery, but instead of copying the forms and production method, they used Roman-inspired motifs, a different stamped decoration method, and a mix of Roman and local pot forms.

Samian production

Samian ware is made in a multi-step process that was used in Roman territory by the 1st century BCE (Webster 1996). British potter Graham Taylor has made many replicas of Samian pottery; click here to see his short video that shows the process, or see below for a summary of the steps involved.

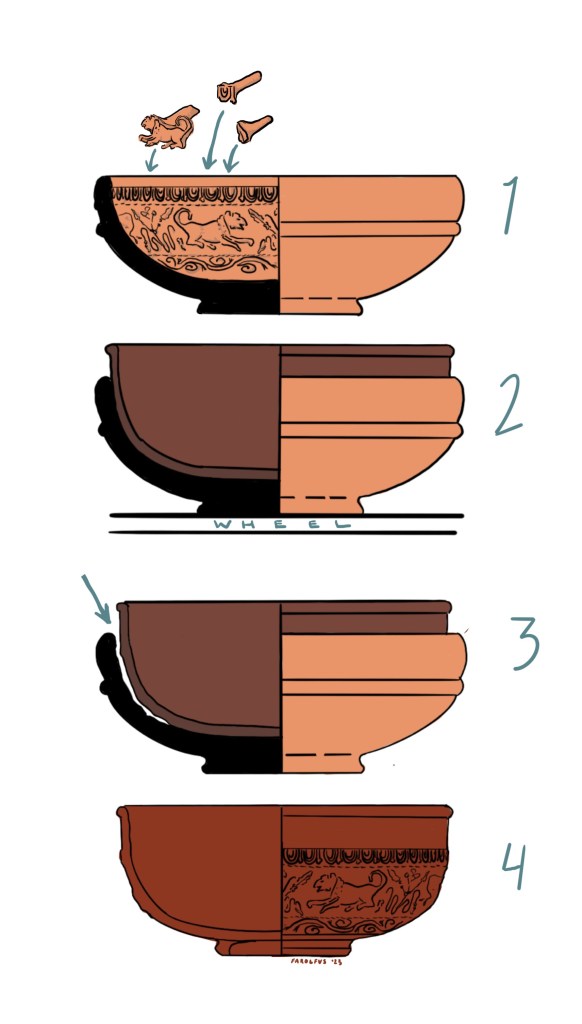

First, the potter used the wheel to throw a bowl-shaped clay form that will serve as a mold. The potter used terra cotta stamp dies, sometimes referred to by the French term poinçons, to decorate the inside of the mold with a pattern. Then the mold was fired (see 1 at right).

To make a vessel, the potter attached the mold to the wheel and pressed fresh clay into it to form a bowl (2). As the wet clay dried, it would shrink and release itself from the mold (3).

The stamped decoration pressed into the mold would appear as raised decoration on the surface of the finished pot, and a foot ring would be added separately (4).

Finally, each pot was given a thin coating of a special “slip”, a very watery clay with all the large particles removed to create a smooth, glossy surface after the pot is fired, similar to a glaze.

This method was ideal for mass-production. A single mold could be used to make hundreds of identical pots much more quickly than if the potter decorated each one by hand, and some pottery workshops in Gaul used kilns that could fire more than 30,000 vessels at a time (Vernhet 1981).

So what is Pannonian Slipped Ware?

To meet demand for new imported wares, potters in Pannonia began to copy Samian ware, producing a high-quality ceramic ware coated in slip. The region already had skilled potters working in the local Celtic tradition, but in response to the arrival of imported Samian ware (and possibly of professional potters who followed the army and set up shop), the Pannonian potters began to make their own terra cotta stamps with shapes and designs that are very similar to Samian ware decoration.

Instead of using these stamps to make a mold, as with Samian ware, the Pannonian potters stamped directly onto the individual pots so that the patterns are impressed rather than in raised relief.

(see Nagy 2014).

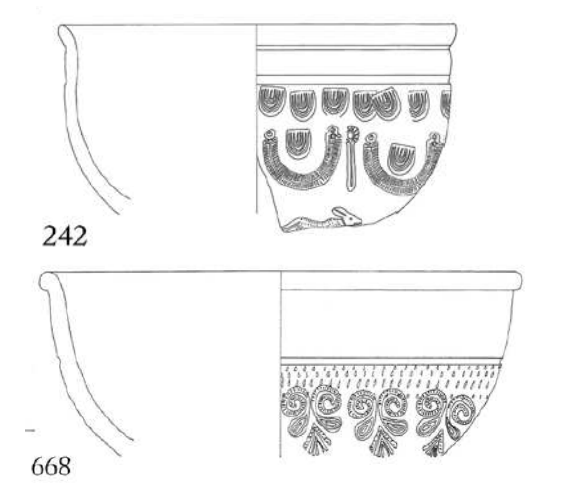

Known as Pannonian slipped ware or Pannonian Glanztonware (the German term for “glossy clayware”), these pots may be red, yellow, gray, or black, but most are gray or black. The decoration schemes sometimes follow the “rules” of Samian ware, but in many cases they use the Samian stamp motifs in totally different ways to create new types of patterns. Samian decoration usually used stamps to create a complex narrative or scene with animals, plants, and human figures arranged in particular ways–for example, hunting scenes with archers and hounds chasing stags or rabbits. Some Pannonian pots imitated these scenes, but most use the same motifs to create more abstract designs or repeating patterns instead. Like the potters who made Samian ware, several of the Pannonian potters also stamped their names into the vessels, and scholars can often attribute vessels to a specific potter or workshop.

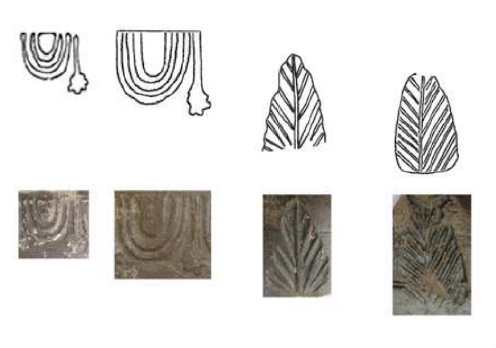

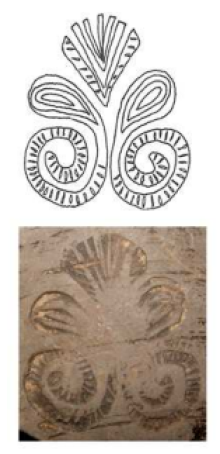

The photograph above shows a Samian ware bowl (courtesy of the Sussex Archaeological Society, CC-2.0). The drawings show Pannonian stamp motifs that are adapted from the Samian designs (drawings from Nagy, 2017).

Pannonian Slipped Ware Stamp Dies

In the Aquincum area alone, potters used hundreds of distinct stamps, although many of them are variations on similar themes . The majority appear to be copied from Samian ware or are simplified versions of Samian designs (garlands, animals, and portrait roundels). Hungarian scholar Alexandra Nagy (2017) has classified the stamp impressions from Aquincum into 25 different broad categories. These include running borders in an abstracted wreath pattern, swags and garlands with pendants, ovolo or egg-and-darts, numerous varieties of leaves and fronds, rosettes, chevrons, diamonds, and human and animal figures. Click here to read the publication in full, and take a look at the stamps catalogued on pages 132 through 164.

INSERT SKETCH OF CATEGORIES

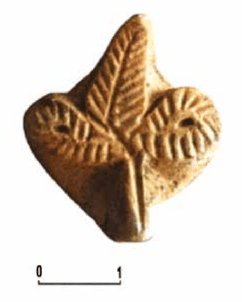

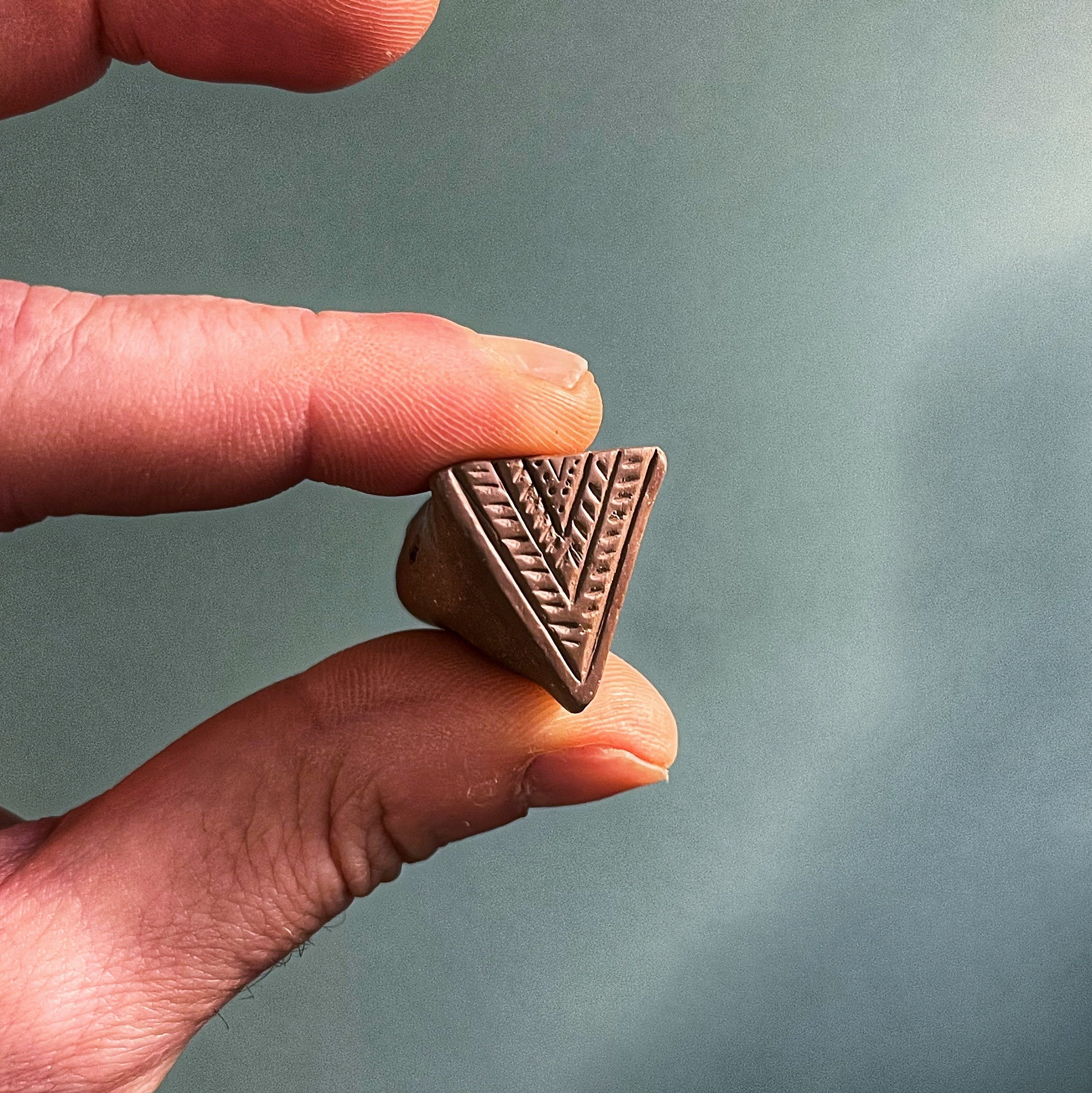

There are multiple surviving examples of the stamp dies themselves (see below). These are generally of unglazed earthenware and have the design carved into one end with a short handle formed at the other end. I make mine by forming the rough shape from wet clay, then waiting for it to partially dry to a “leather-hard” consistency before carving the end into shape with a small knife and using pointed bone and metal tools to cut or impress the details.

At left, a stamp die from the Lágymányos workshop in Aquincum (Nagy, 2017). At right, a trefoil plant stamp die, c.100-150 CE, from Claudium Celeia, modern-day Celje, Slovenia (Krajšek and Žerjal, 2022).

Making a Die

Each die begins roughly formed with a flattened face and a small tapered shaft for handling. Designs are created with point tools and knives, and generally consist of lines and dots, either as distinct design elements or to create textured areas. The process is always subtractive–the flat face remains the highest surface and the design is created by removing material selectively.

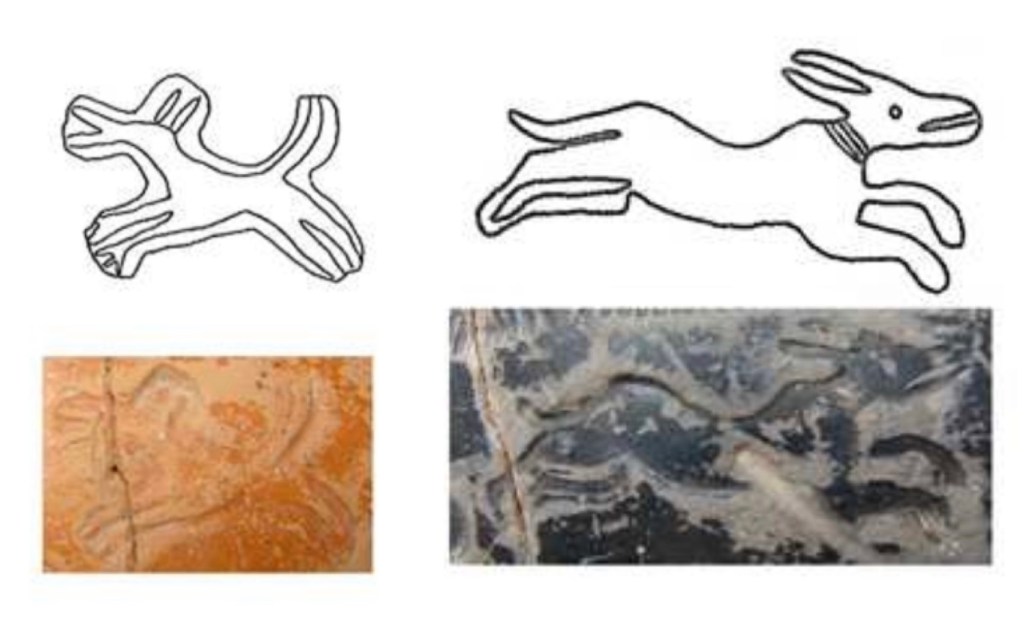

Within those general parameters, die-making seems to have followed one of two possible approaches. In many instances, the stamped face is carved into the silhouette of the motif itself, with additional detail carved away within that silhouette. In others, the die is cut roughly oversized and the motif is carved into it, so that the negative space appears to create a raised impression within the stamped area. The images below show two variations of a running hound and illustrate these two different approaches.

The left-facing hound is recessed into the die face and the surrounding material is carved away to leave a small outline. The right-facing hound is carved as a positive image and the surrounding material is removed entirely. Note: For illustrative purposes, I flipped the images of the original impressions so that it is easier to compare my die to the original–the dies are actually mirror images of the impression on the pot

Version 1: Positive hound, negative die

- The die is formed slightly oversized and the shape of the dog is carved in with the pin tool

- The dog’s head and torso are carved into the surface to create a recessed shape

- Large areas of excess material are cut away with a knife

- Remaining material is carefully scraped away until it creates an outline.

Version 2: Negative hound, positive die

- The rough outline is lightly sketched onto the surface

- The surrounding material is carved away to a depth of approximately 5mm

- Fine details are added, such as the collar and eye

How are the Pannonian dies different from Samian dies?

A Samian stamp die is a positive design that is used to create a negative impression in a mold, so that the design on the finished pot is positive. So the Samian dies are essentially “WYSIWYG”–the stamp die itself is exactly what will appear on the surface of the finished pot, so the die maker needs to carve the detail precisely the way they want it to look. In contrast, a die made for direct stamping, as on Pannonian Slipped Ware, is the exact opposite of what will appear on the pot, so the die maker has to mentally reverse the high and low areas, left and right directions, and think about how light will hit the recessed impression.

The shapes of the stamp dies are slightly different because the designs are meant to be recessed; they need to have crisp outer edges to show off the design, and are not rounded like Samian dies. They have flatter faces with positive and negative space instead of a more multi-dimensional design.

Potter’s Toolkit

In order to make sure that I was working within the parameters of a period potter, I felt it was important to make my dies using the tools that would have been available to a Roman provincial potter in the early 2nd century CE. There are any number of ways to carve them, and while some modern ceramics tools are timeless, others are decidedly newfangled and have no historical analogs in late antiquity.

So precisely what tools would a potter have had on hand? The information below provides much more detail, but the gist of it is this: archeological evidence from other pottery production sites in Roman provinces indicates that potters frequently repurposed other items–particularly hair/dress pins and writing styli–as decorating tools. My toolkit includes replicas of a knife and several bone pins found in the eastern potter’s quarter of Aquincum, as well as a few other “repurposed items” that are found in abundance elsewhere in the settlement.

Material evidence

For the antler stamp dies I have made in the past based on slightly later northern European finds, there is a reasonably good body of evidence for the tools a typical boneworker would have used. We also have parallel industries that help to support the availability and use of the tools; bone and antler combs are one such example. The ring and dot auger, saw, and drill used to make and decorate combs can produce just about any of the common pottery stamp motifs. While extant pottery dies are not necessarily abundant, bone combs certainly are, and examining them closely can give a good idea of the size and width of saws, ring and dot tools, and drills that were available in period for making antler dies in northern Europe.

In the case of the provincial Roman stamp dies, however, the die itself is made from the same raw material with which the potters worked. In fact, evidence from excavations of potters’ workshops elsewhere in the Roman provinces (see Mackenson 2009; Murphy and Poblome 2012), shows that potters routinely made many of the tools and pieces of equipment used in the production process from clay–including bats, kiln components, funnels, moulds, and stamp dies. While the relationship between northern European potters and boneworkers is unclear (did some of the potters make their own dies, or was this usually done by antlerwork specialists, comb-makers, etc.?), it is reasonable to conclude that the Pannonian potters (or a subset particularly skilled in this task) made their own dies, and likely would have used the same tools they had on hand for other applications in clay. But what tools might they have used?

The extensive excavations of another large provincial Roman pottery workshop complex in Sagalassos in southwestern Turkey provide extremely valuable insight into this question. Most notable is the fact that the Sagalassos potters predominantly used found or repurposed items as tools. In some cases, these tools would not necessarily even be identifiable as potters tools if not for the context in which they were excavated.

The Potters Quarter at Sagalassos produced decorated red slipware for a period of several centuries, and to date more than 80 excavated items have been classified as potters tools, not including molds or wheels (see Murphy and Poblome 2012). The most common hand tools at Sagalassos are ribs (11 examples), point tools (19 examples), fettling knives (11 examples), and polishing pebbles (13 examples).

- Ribs: Although some ribs were purpose-made from clay and fired, many were made from sherds of already-fired pottery or from scraps of iron or bronze sheet, in one case still bearing a fragment of a dedicatory inscription from its previous use.

- Point tools: these are also generally repurposed items and nearly all are identifiable: a mix of iron hairpins and needles, iron styluses, and worked bone hairpins. Murphy and Poblome successfully matched the impressions of these items with decorative marks on pottery molds from the site, so these are not random items accidentally lost or discarded in the workshop.

- Fettling knives are another common tool in both the ancient and modern potter’s toolkit. These are used for cutting and trimming clay, and the Sagalassos examples are typically long thin iron blades with a straight or slightly curved cutting edge and a wood or bone handle. Interestingly, one is extremely similar in shape and design to the Roman penknife–perhaps another repurposed item? (cf. Fig. 2-h in Murphy and Poblome and Božič 2001, 28 Fig. 1)

When compared to the finds of various objects from the pottery workshops of Aquincum (based on review of items with digital images in the Hyperion database), some patterns emerge. In the eastern potter’s quarter, finds include several finished vessels, as well as molds and dies used for production, three iron trowels, and three small knives with blade lengths of 16cm, 13cm, and 10cm, all of which have a straight or slightly curved cutting edge. One in particular is startlingly similar in shape to a modern fettling knife, and this shape may be the result of repeated sharpening gradually wearing down a large portion of the blade. I commissioned a reconstruction from a cutler friend; it matches the dimensions of the original and has been extremely handy.

The finds from the eastern Potter’s Quarter also include multiple bone hairpins (see reference list for links to examples); all are plain, and sharpened to varying degrees at the narrow end; the wide end may be conical or rounded. These are very similar to the numerous bone hairpins found elsewhere in Aquincum, in both the military and civilian settlements. These bone pins are generally between 10 and 14cm, although the ones from the eastern potters’ quarter are very plain and lack the decorated ends found on some examples from other sites in the area. Whether this is because the potters reshaped the wider ends of broken or discarded hairpins or simply used the plainer ones that belonged to members of their own families is unknown. I made several hairpins from cattle bone with a range of conical and rounded butt ends that match the finds from the eastern potter’s quarter.

The knife and the bone hairpins are actually enough to reconstruct nearly all of the stamp dies on display here; a bronze dress pin is the only other item used. While I am not aware of any catalogued in the potter’s quarter specifically, broken fibula pins are another fairly common find in Aquincum as well, and I use a bronze pin and a replica of a bone writing stylus to augment my toolkit.

Proof of concept

The final step in this project is to test out the stamp dies on actual vessels. The original pots were made from earthenware and coated with a very fine slip referred to as terra sigillata (a watery clay with all but the finest particles removed). This acts somewhat like a glaze, helping to seal the surface of the pot and adding shine. Pannonian Slipped Ware was produced in a range of colors, typically in the

red/orange and gray/black spectra. The color was formerly believed to be entirely controlled by the oxidation/reduction firing atmosphere, but a more recent study found that the red color of Gaulish terra sigillata is dependent on the hematite crystal size in the slip itself (Sciau et al., 2005).

Since the stamped impressions are coated with terra sigillata, I wasn’t sure that I could rely on my quick tests on fresh clay to indicate whether my dies were crisp enough. I made some test pieces first, dipping half of each one in terra sigillata to

see how much detail would be lost when the impressions were coated. It turned out that the coating “breaks” or thins itself out on sharp edges much like a modern glaze does, so that it only really pooled in larger recessed areas and did not blur the details of the impression like the delicate hatching on the leaves or the rabbit’s fur (see below).

Armed with the confidence that this was probably going to work, I made a couple of actual pieces. These demonstrate the hasty, haphazard placement of stamps found on many of the originals:

Bibliography

Adler-Wölfl, K. 2004 Pannonische Glanztonware aus dem Auxiliarkastell von Carnuntum: Ausgrabungen der Jahre 1977-1988, Vienna: Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_477713

Božič, D. 2001: ‘Über den Verwendungszweck einiger römischer Messerchen’, Instrumentum 13, 28–30.

“Hairpin (Hyp-4508)”, in Á. M. Nagy et al. (eds), Hyperión. A database of classical studies (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2003‒).

URL: http://hyperion.szepmuveszeti.hu/en/targy/4737 (Accessed: February 2023).

“Hairpin (Hyp-4509)”, in Á. M. Nagy et al. (eds), Hyperión. A database of classical studies (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2003‒).

URL: http://hyperion.szepmuveszeti.hu/en/targy/4738 (Accessed: February 2023).

“Hairpin (Hyp-4512)”, in Á. M. Nagy et al. (eds), Hyperión. A database of classical studies (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2003‒).

URL: http://hyperion.szepmuveszeti.hu/en/targy/4741 (Accessed: February 2023).

“Knife (Hyp-3236)”, in Á. M. Nagy et al. (eds), Hyperión. A database of classical studies (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2003‒).

URL: http://hyperion.szepmuveszeti.hu/en/targy/3453 (Accessed: February 2023).

Leleković, T. 2018. ‘How were Imitations of Samian Formed?’ Internet Archaeology 50. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.50.18

Krajšek, J. and Žerjal, T. 2022. ‘Celeian Slip Ware: Pannonian Slip Ware (PSW) from Celeia: the evidence from the Mariborska cesta site in Celje, Slovenia’, in Ožanić Roguljić I. & Raičković A., eds. Roads and rivers, pots and potters in Pannonia – interactions, analogies and differences. Zagreb: Institut za arheologiju.

Mackensen, M. 2009. Technology and organization of ARS ware production-centres in Tunisia. In J.H. Humphrey (ed.), Studies on Roman Pottery of the Provinces of Africa Proconsularis and Byzacena (Tunisia). Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 76: 17-44. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology

Murphy, E. & Poblome, J. 2012. Technical and Social Considerations of Tools from Roman-period Ceramic Workshops at Sagalassos (Southwest Turkey): Not Just Tools of the Trade?. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology. 25. 69-89.

Nagy, A. 2014 ‘Forging samian ware in the Pannonian way: the case of stamped pottery’, Rei Cretariae Romanae Favtorvm Acta 43, 119-27.

Nagy, A. 2017. Resatus and the stamped pottery. Aquincum Studies 1, Budapest.

Nagy, A. 2016. Vessels with planta pedis stamp in the area of Aquincum. Communicationes Archaeologicae Hungariae. 2016. 209-234.

Peacock, D.P.S. 1982. Pottery in the Roman World: An Ethnoarchaeological Approach. London: Longman.

Sciau, P., Relaix, S., Kihn, Y. & Roucau, C. “The role of Microstructure and Composition in the Brilliant Red Slip of Roman Terra Sigillata Pottery from Southern Gaul.” Materials Research Society Proceedings Vol. 852, 006.5.1-6, 2005.

Vernhet, A., 1981. Un four de la Graufesenque (Aveyron): la cuisson des vases sigillés. Gallia 39, pp. 25–43.

Webster, P. 1996. Practical Handbook in Archaeology 13: Roman Samian Pottery in Britain, Council for British Archaeology. Reprinted 2005.