Submitted for Northshield Kingdom A&S, A.S. LIV (February 2020)

OWNERSHIP, COPYRIGHT, & DISCLAIMER

All work and documentation shown here is the work of Farolfus filius Richardi (mundanely S. Renfield), from the Barony of Nordskogen, Kingdom of Northshield, in the Society for Creative Anachronism. The SCA is a 501.c.3 charitable organization dedicated to pursuing research and re-creation of pre-seventeenth century skills, arts, combat and culture.

The text below was originally submitted with a competition entry and was not intended for publication or distribution, so some images (from archaeological reports etc.) have been removed, as I do not hold the copyright – I am in the process of re-drawing them myself for online use. In the meantime, please use the contact link on this page to get in touch if you would like more information on the redacted images or if you would like to use my photographs and research for non-profit use within the SCA – I am happy to share as long as I am properly credited.

Scroll down if you want to start with all the “what and why” stuff at the beginning, or CLICK HERE to go straight to the “how I made the thing” part.

Introduction

This project endeavors to construct a plausible sheath for a Langobardic short seax of the mid-7th century – specifically, one suited for a replica of the seax blade found in Grave 10 of the Langobard necropolis at Montecchio Maggiore in the Veneto region of northern Italy. This posed something of a problem, as no single extant find could serve as the basis of a complete reconstruction. A literature review and examination of the grave goods in several major Langobard burial sites produced little in the way of direct evidence. Leather finds associated with Langobard seaxes are too fragmentary to confidently reproduce an original example. Metal fittings are often the only remnants that survive, and while some highly-decorated fittings (such as the dagger mounts from Castel Trosino now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum) provide a sense of the shape of the now-decayed sheath, these are clearly Byzantine in design (Barbieri, 151). Reconstruction of a sheath for a Germanic type of sidearm from a Langobard context proved more difficult.

In the absence of a single surviving, complete example, I examined grave finds from Langobard necropoli at Montecchio Maggiore, Trezzo sull’Adda, and Nocera Umbra consisting of metal sheath fittings with some traces of organic materials. To aid in the interpretation of the metal fittings and consider construction and decoration methods, these finds were supplemented with surviving leather sheaths from contemporary neighboring Germanic groups including a 7th-century Frankish sheath from the basilica of Saints Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg, Germany, another example in the B.A.I. Collection in Groningen, Netherlands, and review of photographs of an assortment of Frankish and Alemannic sheathes in the Romer Germanen Museum in Cologne, Germany. Other extant seax sheaths produced several centuries later, including those found in Dublin, York, and other Anglo-Scandinavian contexts, were considered as a frame of reference for construction and leather tooling methods as well, including examples from the 9th century onward documented in Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York. Decorative motifs are conjectural but are based on surviving Langobardic metalwork decoration from the same time period and arranged to form an overall design composition informed by the Augsburg sheath and other examples in the Romer Germanen Museum.

Historical Overview

In his 6th-century history of the Frankish people, Gregory of Tours supplied the term “scramasax” to describe the weapons wielded by two young assassins: “…duo pueri cum cultris validis, quos vulgo scramasaxos vocant,”- literally, “two boys with powerful knives, which they commonly call scramasaxos” (Historia Francorum, IV). Larger than the knives used for eating and other utilitarian tasks, this type of single-edged weapon was widespread among continental Germanic groups in the Migration Period, including the Saxons, Langobards, Alemannii, and Franks. Seaxes appear in graves alone and alongside swords (spathae), and the scramasax was commonly found in Langobard burials from the late 6th through the 7th century (Rigoni and Bruttomesso, 51).

The specific form of the weapon itself varies across time and geography; an in-depth discussion of blade typology is outside the scope of this project, but whether the earlier spear-point model (as seen in this project) or the later “broken-back” model found in various Anglo-Saxon and Viking contexts, some uniform characteristics of surviving sheaths are germane. Examples from the 7th through 10th centuries typically consist of a single piece of leather folded in half, with the edge secured by stitching, riveting, or both. Some surviving Continental examples (Langobardic and Frankish) have traces that indicate wooden cores (see Roffia, 69; Ypey, 216; and Werner) and were secured with a combination of small bronze rivets and large bronze studs along the outer edge. A 6th or 7th century Frankish grave marker from Niederdollendorf (Figure 1) shows a figure wearing just such a weapon, and the dots along the sheath’s upper edge can easily be interpreted as decorative studs or rivets.

While research did not indicate the precise methods by which seaxes were affixed to the wearer’s belt, positioning of hardware (or in the case of the Groningen sheath, paired slits) strongly suggests a two-point attachment to the sheath itself, and Langobard necropoli at Nocera Umbra, Montecchio Maggiore, and elsewhere frequently yield paired metal belt fittings with slots. Coupled with artistic depictions such as the Niederdollendorf and Repton Stone, these factors support some form of two-point suspension in which the seax was worn more or less horizontally.

Summary of supporting archaeological finds

Two grave finds from the Langobard necropolis located on the present grounds of a hospital in Montecchio Maggiore serve as the basis for the subject piece but are limited to the blades and associated hardware and lack substantial organic components. In order to determine an appropriate means of constructing and decorating the sheath and to assist in interpreting the hardware, I relied on two surviving leather seax sheaths from neighboring Germanic groups that date to the appropriate time period and would have contained similar weapons. The following section summarizes these four examples.

Grave 10, Montecchio Maggiore

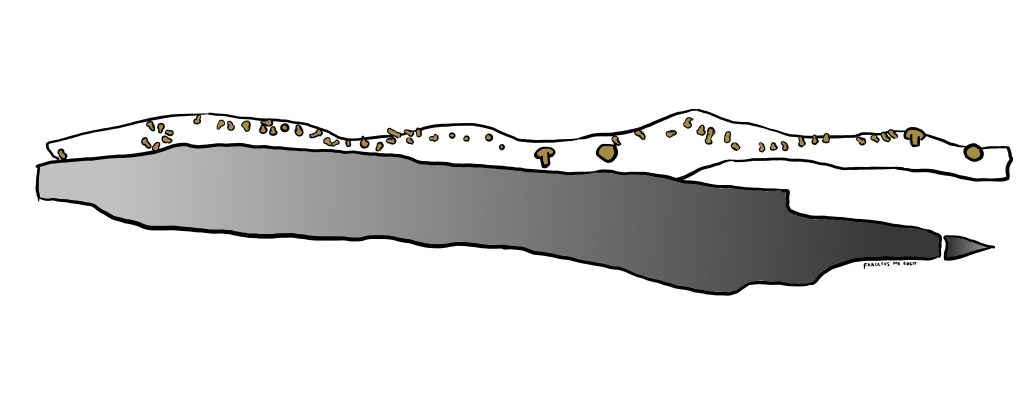

The proposed reconstruction was designed to fit a replica of the surviving blade from Grave 10 and uses the same combination of metal fittings (see Figure 2). Grave 10 contained the remains of a seax blade approximately 29 centimeters long overall by 2.6 centimeters wide (11.4 inches by 1 inch). Fittings associated with the blade include four large bronze studs with truncated conical heads roughly 1 cm in diameter and 8 mm long and a group of twelve small rivets 4 mm long and 1 mm wide with a circular cross-section and flattened hemispherical head (Rigoni and Bruttomesso, 31).

Grave 11, Montecchio Maggiore

Grave 11 contained a seax blade 44.5cm in length overall, as well as a group of four large studs and 120 small rivets (Rigoni and Bruttomesso, 31). At the time of excavation, the bronze fittings in Grave 11 were found arranged in a single line along the outer edge of the sheath, with the four larger studs grouped in pairs near the opening and the midpoint, suggesting a two-point suspension affixed to the sheath at these points (see Figure 3). Laboratory analysis indicates that the sheath was of leather, with a possible fur lining (Rigoni and Bruttomesso, 40).

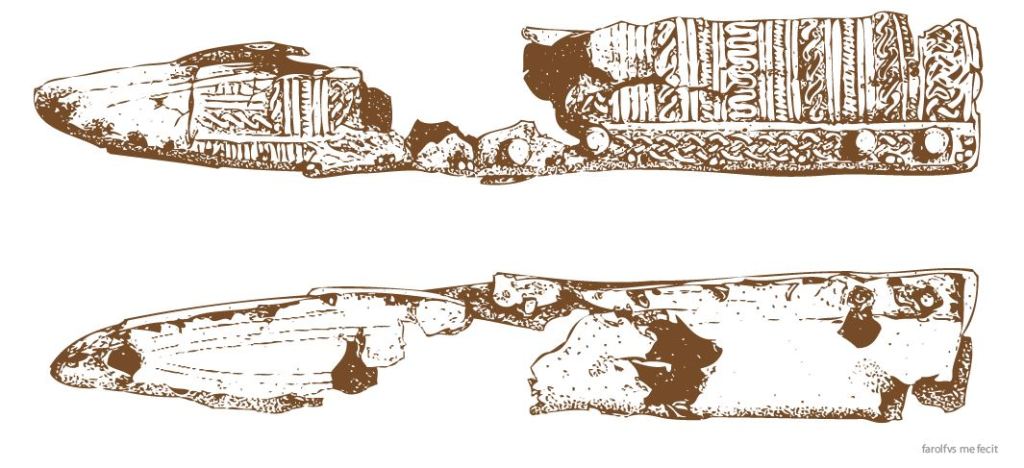

Grave 8, Basilica of Ss. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg

The similarity in scale and associated hardware of this 7th-century Frankish seax sheath make it a useful comparison by which one might reconstruct the Montecchio Maggiore Grave 10 sheath. Augsburg was located on a major transalpine route from nearby Verona (the Via Claudia Augusta through the Brenner Pass), and geographically speaking, the Augsburg material is a much closer comparison from which to draw upon than contemporary examples from Scandinavia or the British Isles. The Augsburg sheath (see Werner) is 26 cm long and has its outer edge secured with small bronze rivets and two pairs of larger bronze studs positioned at the mouth and midpoint of the sheath’s edge, a collection of hardware very similar to the Montecchio Maggiore Grave 10 example. The 23cm blade has a cutting edge approximately 17.5cm long, which retained traces of softwood (“Nadelholz”), indicating the presence of a thin wooden core around which a cowhide exterior was wrapped.

The surface is tooled in narrow bands running perpendicular to the edge and uses alternating serpentine motifs with a simple knotwork pattern along the edge. Where the design is forced to conform to the shape near the tip, a separate motif is oriented parallel to the blade. The reverse side does not display tooling aside from a few lines delineating the shape of the blade. Examination of photographs of the piece (see Figure 4) shows that the decoration was likely impressed into the damp leather using a slightly blunted tool and does not appear to be incised. This technique was the most commonly used decorative technique noted at York as well and appears to have been widespread for sheathes in the Anglo-Scandinavian sphere as well (Mould et al., 3263). No impressions on the surface of the leather indicate the use of visible stitching, indicating that the sheath was closed either by means of the edge riveting alone or by using a tunnel stitch (published descriptions do not mention any stitching and photographs do not show the interior).

Seax sheath, Collection of the BAI in Groningen, Netherlands

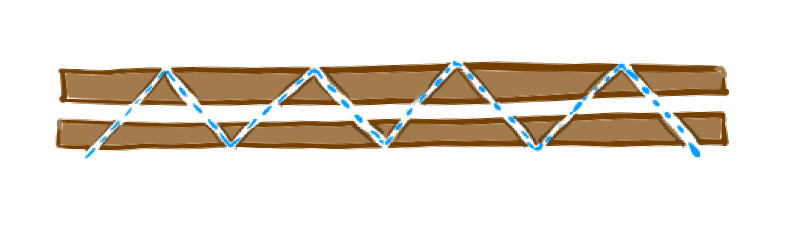

The original finding context is unknown, but the sheath is exceptionally well preserved and has been dated based on the decorative motifs on the leather, which occur on inlaid iron buckle plates from elsewhere in the Netherlands, dated to the first half of the 7th century CE (Ypey, 217). The sheath consists of a leather exterior around a softwood core and was closed with a combination of rivets and stitching. Two sets of paired slits are found along closed edge of the sheath. While the decorative motifs show that the 35cm sheath was once longer and was cut down at some point to hold a shorter weapon (a 28cm blade), the state of preservation is such that the stitching method can be clearly understood; according to archaeologist Jaap Ypey:

Each slit at the surface splits in two slits, which are roughly perpendicular to each other, and make an angle of 45 degrees with the surface, so a zigzag line appears. Through this the thread was pulled to close the cutting edge side of the scabbard (213).

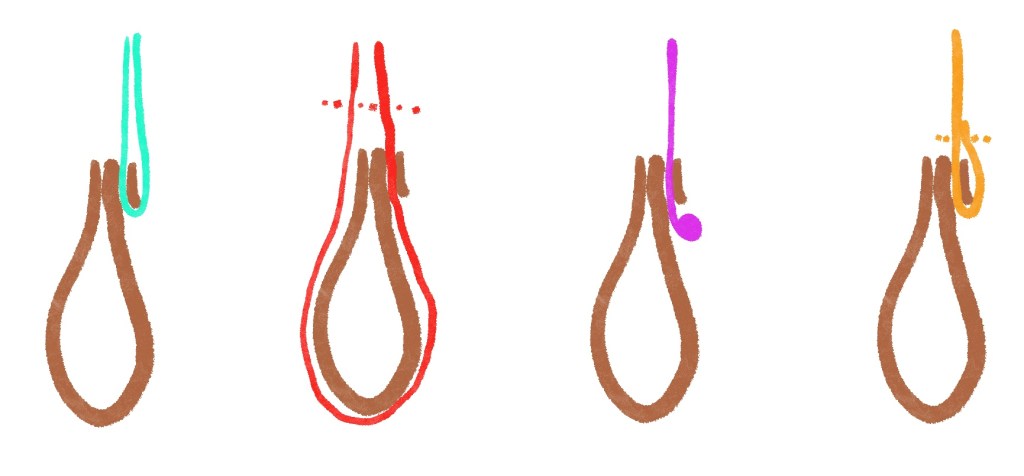

In essence, the closure is sewn much like a tunnel stitch, although a very small portion of the peak of each “tunnel” would be exposed on the surface of the leather (see cross-section diagram below).

Materials and Design

Given the aforementioned evidence, I approached the project with the following basic parameters: the sheath should be a single piece of folded leather, possibly with a wooden core, secured along the upper edge with hidden stitching, closed with four large studs and twelve small rivets, and allowing for two-point suspension. It should be decorated using a slightly blunted tool on damp leather rather than the various incised and seeded/beveled methods that appear in the 11th Century CE and persist through medieval and modern leather decoration (Mould et al., 3263–64). The decoration should use motifs found on belt hardware from the same time period and culture. The following section discusses the materials and techniques used and their justification.

Leather

The use of cowhide is supported by the Augsburg sheath. The thickness was determined based on the length of the surviving small rivets from Grave 10 at Montecchio Maggiore (4mm), which would have passed through a double-thickness of the leather, requiring the use of a folded piece of 2-3mm leather. This also correlates with the thickness of the Groningen sheath[14] and that of another Langobard sheath from Grave 5 at Trezzo sull’Adda, where a remnant of a seax sheath’s closure/upper edge was found preserved as a strip of leather 5 to 6mm thick pierced by small rivets, indicating the use of a folded sheet of leather 2.5-3mm thick.[15] Mould et al. note the use of thick leather of up to 3mm for seax sheathes in York several centuries later as well.[16] Therefore 6-7 oz. (average 2.8mm) vegetable-tanned cowhide was selected as a readily available material that matched the documentable thickness and species of multiple 7th-century examples. Vegetable tanning is a method well documented within the appropriate time period, and the alternate period-appropriate method (alum tawing) produces a softer product less suitable for tooling.[17]

Thread

Historical examples were stitched using waxed linen or wool, thin leather thong, or sinew, but these materials rarely survive and research did not indicate with certainty what type would be most accurate.[18] As the stitching is completely unseen, heavyweight two-ply linen thread impregnated with beeswax was used as a “best guess” using materials documented in a slightly later period and known to be available in Langobard-occupied Italy in the mid-7th century.[19]

Hardware

The four large studs are commercially produced brass dome-headed rivets similar in dimension to the Grave 10 studs, filed down to the appropriate truncated-conical shape and peened over on the back side of the sheath. The smaller rivets are made using commercially available brass escutcheon pins cut to length, which otherwise match the shape and dimensions of those found in Grave 10. No materials were found that could be interpreted as washers or any sort of backing, but when placed outside the stitch line (as is the case on both the Groningen and Augsburg sheathes), the small rivets may have been more decorative than structural. When installed, the rivets were crimped slightly on the reverse side of the sheath, the apparent technique in photos of the Augsburg sheath (see Figure 4). The rivets are installed in pairs, echoing the layout found on both the Augsburg and Groningen examples that use small groupings at intervals along the outermost edge. Although the Montecchio Maggiore fittings are of bronze, I was not able to obtain appropriate reproductions and thus substituted brass as a more accessible copper alloy that would produce a similar appearance and would not affect the construction or functionality of the finished item.

Suspension

The suspension method utilizes the two-point method involving a strap near the mouth of the sheath and another near the midpoint. The Groningen sheath supports the two-point suspension based on the paired slits in the closed edge of the sheath, but lacks the large studs found on the other examples previously cited. This begged the question of whether the studs were purely ornamental or were actually used to anchor a strap. I consulted several other Langobard finds to determine whether any other supporting information was available but found no definitive answer. Rigoni and Bruttomesso (52) note that among the examples documented from Langobard graves at Trezzo sull’Adda, the fittings from Grave 5 suggest that paired studs secured two “passers (passanti), perhaps made of leather” that held the suspension straps. The most clearly preserved examples of this strap holder concept among the group of sources for this project were those found along with another partially preserved sheath from Ss. Ulrich & Afra in Augsburg, although numerous similar fittings have been recovered elsewhere. In Augsburg, Werner (176) notes that two 3.7cm long iron strap holders were affixed to the back of a sheath’s upper flap and could accommodate 1.5cm straps for a two-point suspension (see Figure 6). Within a Langobard context, Tomb 3 at Trezzo sull’Adda contained a seax 44.5 cm in length, dated to the first half of the 7th century; the sheath remnants included a pair of small u-shaped suspension brackets mounted at the edge (Roffia, 52). While the Groningen example uses paired slits, it does not include large studs; conversely, the Ss. Ulrich & Afra Grave 8 example with large studs does not appear to have any slits between them. Given the limited evidence, I elected not to use slits and instead look for a way of attaching suspension strips using the studs.

Under closer scrutiny, the hardware from Grave 10 at Montecchio Maggiore raised the possibility of what Rigoni and Bruttomesso term “passanti.” The four studs have some variation in the extant shank length, but based on the scaled drawings, appear to have up to 7mm of shank between the underside of the head and the mushroomed portion at the tip which would have secured the stud in position. The discrepancy between this length and that of the smaller rivets (4mm) may be explained by increased corrosion of the more fragile rivets but may also indicate the use of some additional material of 1-3mm thickness along the closure edge that has not survived. One possibility is that a bronze or iron washer of some sort was used on the back side of the closure but has corroded, despite the survival of the blade and other metal fittings. Another possibility is that the additional material was organic, such as a strip of leather used to create an attachment point for suspension straps. This possibility, coupled with Rigoni and Brutomesso’s suggestion, prompted me to choose the latter interpretation. To do so, I added a strip of 5-6 oz leather between each pair of studs, affixed to the back of the sheath leather after the Augsburg example. This seems to work and provides an attachment point that does not require cutting slits or integrating the straps into the closure stitching, making it easy to repair or replace a broken strap.

Figure 6. Iron strap holders from Augsburg. Drawing based on Werner (Pl. 43)

Inner core

[NOTE: since this project was completed, a new volume by Olaf Goubitz and Marquita Volken entitled ‘Covering the Blade’ has been published. It provides a great deal more information on seax sheath cores than I had available, and includes evidence of multilayered cores with hair-on hides, rawhide/parchment, and wood lath, any or all of which could be laminated within the outer leather cover – I have tried each of these out and they all work very well].

Although the two well-preserved examples from neighboring cultures appear to have had some sort of wooden core, the exact nature of this core is unknown. The wood species was not identified in any of the available literature beyond “softwood.” The example from Tomb 5 at Trezzo Sull’Adda appears to have had a wooden core,[23] but no mention is made of traces of wood in the documentation of the examples from Montecchio Maggiore, where organic material survival seems to have been rather less common. At Nocera Umbra, a 22cm seax in Grave 76 was found to have traces of leather on the blade,[24] suggesting a lack of a wood core. This example is rather shorter than the others, leading me to suspect that there may have been some size-based distinction. At 22 cm including the tang, it would be unlikely to have a blade exceeding 16 or 17 cm. Of the documented examples with traces of wood cores discussed herein, none appear to have contained a blade with a cutting edge of less than 17 cm (and several were nearly twice that length).

I would be tempted at first to draw a distinction between the 40+ cm long seaxes, which clearly live in scabbards, and the short seaxes that might live in sheaths, but the Augsburg example indicates that a wood core was considered appropriate for a blade with a 17.5 cm cutting edge. The blade from Montecchio Maggiore Grave 10 has a cutting edge nearly 23 cm in length, placing it within the range of those with wooden cores, and within a culture known to use wooden cores. I therefore elected to construct this project with a wooden core. Werner describes the core of the Augsburg seax sheath simply as “Nadelholz” (coniferous wood). However, given the impossibility of drawing any conclusions about softwood vs. hardwood, let alone species, from the limited examples, poplar was selected as a species of easily workable wood that is documented in Langobard contexts for parade shields and knife handles.[25]

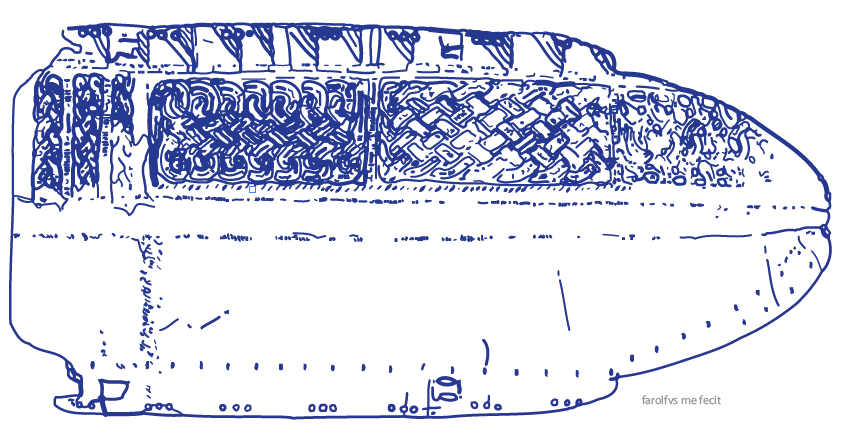

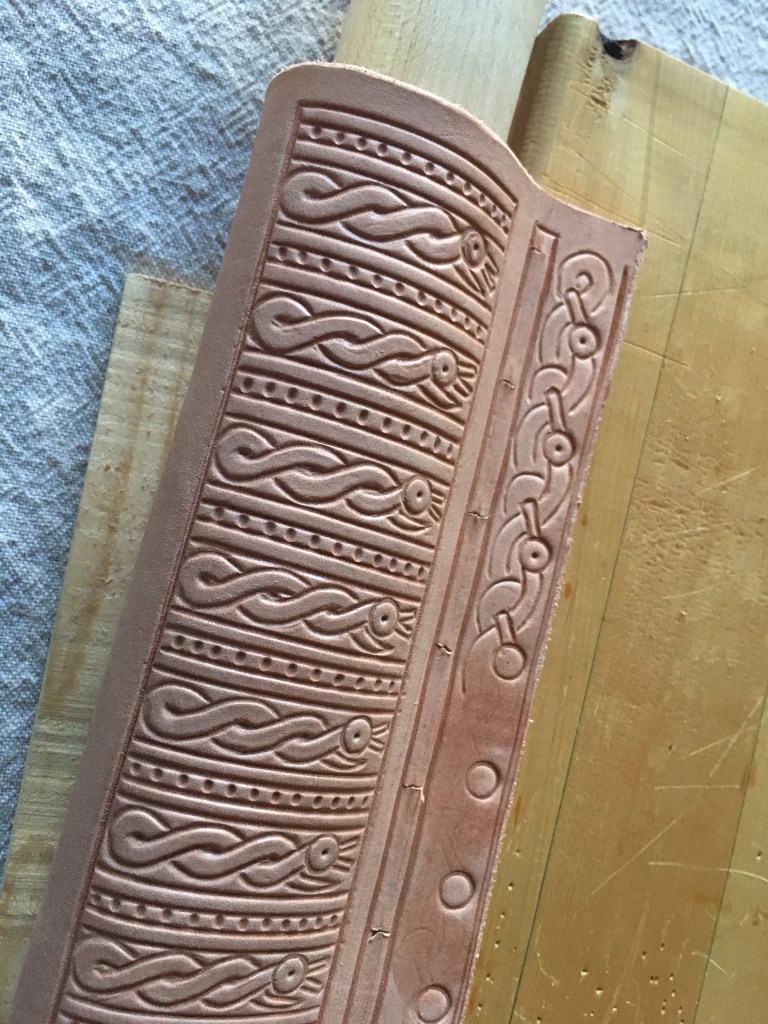

Decoration

Ypey’s study noted that the leatherwork decoration on the Groningen sheath was comparable to the motifs found on inlaid iron buckle plates from elsewhere in the region.[26] I therefore elected to use contemporaneous metalwork as a plausible source for my decoration as well. Several examples of inlaid ironwork found in 7th century Langobard contexts were used as inspiration for the tooling motifs. These include the decorative belt hardware also found in Montecchio Maggiore Grave 10 itself (Figure 7), along with a buckle (dated between 590 and 610 CE) from Cividale del Friuli (Figure 8). These simple motifs consist of stylized interlocking serpent-like forms with large round eyes and short, simplified “beaky” mouths that could be broadly classified as Salin Type II zoomorphic designs.[27] Images showing decoration on a set of spurs from Trezzo sull’Adda (Figure 9) and strap ends from Nocera Umbra (Figure 10) are provided as additional examples of the use of simple beast heads and twisted forms to fill all available space.

Although excavated from sites that are hundreds of miles apart, the pieces all use similar motifs – evidence in my mind, at least, that these motifs would have been fairly common and would be an appropriate choice of inspiration. Unlike later Viking-Age examples from York and Dublin that divide decorative motifs into distinct blocks that correspond to the blade and grip,[28] the Augsburg sheath instead displays repetitive perpendicular bands for much of its length, and my decoration follows this layout as well. The majority of the decoration incorporates the single twisted-serpent motif from the Grave 10 belt hardware, while the tip and upper edge use designs from the Cividale del Friuli buckle. As with both the jewelry and leather examples, my design attempts to fill all available space on the visible surface of the sheath, using dots and lines to break up the knotwork motifs.

Figure 7. Belt hardware decoration, Grave 10, Montecchio Maggiore. Drawing from Rigoni and Bruttomesso.

Figure 8. Drawing of buckle from Cividale del Friuli, dated 590-610 CE; buckle frame motif is the source for the upper edge decoration on the sheath, while the motif at the sheath tip is adapted from the buckle plate design. Here is a photograph of the original buckle.

Figure 9. Detail of a spur from Grave 4, Trezzo sull’Adda showing use of animal heads in a running band. Drawing from Roffia.

Figure 10. Strap ends from Nocera Umbra, Grave 20, showing use of twisted form to completely fill space. Drawing from Rupp.

Tools and Construction

The project required three types of tools; those for cutting/punching leather, those for decorating the leather, and those needed to carve the wooden core. The leatherwork was accomplished using period-appropriate tools, while the brief woodworking task was done with modern hand tools as similar as possible to historical examples.

Core

The wooden core was cut from an oversized poplar board (crosscut to length using a coarse-toothed modern handsaw). The interior was hollowed out with a modern sweep chisel (Fig. 11) and the exterior was shaped with a small modern hatchet (Fig. 12) and drawknife, and finished with a flat chisel. Without any surviving evidence for this conjectural component aside from scabbard cores from other cultures and later periods (which seem to include additional layers of sheepskin lining and textile wrapping not accounted for in the documentation of surviving seax sheathes and thus may not be comparable), I cannot speculate as to the “accurate” method for the mid-7th century but attempted to use tools that were not substantially different in design from their historic counterparts in either the earlier Roman era[29] or the later Viking-age tools from the Mastermyr Chest. The modern tools offered no distinct advantage in either their shape or other properties (any benefit of modern alloy would be negligible for a brief task in a soft, easily workable wood.)

Figure 11. Sweep chisel used for hollowing out one side of the core.

Figure 12. Hatchet used for shaping the exterior of the core.

Leatherwork

The cutting, trimming, and punching of the leather was accomplished entirely using handmade tools based on extant examples that either pre- or slightly post-date the desired time period (see Figure 13). Forged by Daegrad Tools in Sheffield, UK, the lunette is modeled on examples from late-Roman Saalburg, Germany and Anglo-Saxon West Stow, UK. The awls are based on examples excavated in Anglo-Scandinavian York.[30] When carefully sharpened, these tools were amply sufficient for all the required cutting, punching, and skiving tasks.

Figure 13. Large and small awls and lunette knife.

For decoration, I used a small group of bone tools that I made from cow bone. These fit the brief as described by Mould et al. for a “blunt-ended tool [drawn] with downward pressure across wet leather” and are not dissimilar to some examples of bone tools from Orkney at the National Museum of Scotland; believed to be leatherworking tools, these are displayed in a grouping dated between the 1st and 9th century CE (Figure 14), and include two blunt-tipped tools. A burnished bone point found in the early Medieval site at Llangorse Crannog in Wales is also believed to be a possible leatherworking tool.[31] I found that a small blunt-tip (round in cross-section), a hollowed bone forming a ring, and one that was slightly chisel-tipped (similar to the largest in Figure 14), were all that were needed to execute the design. The leather was dampened slightly, the blunt tool was used to lightly sketch a design and impress any dots. A piece of scrap wood served as a straight-edge for longer straight lines and the hollowed ring was used to impress the circles for the beasts’ eyes. The slightly chisel-tipped tool was used to draw the linear portions of the design. The motion required to do the latter took a bit of getting used to – the tool has to be rotated between thumb and forefinger while also applying pressure and finding the balance between the two was not easy. When successfully executed, the result is that the base of the groove is slightly burnished and the sides of the tool tend to create a slight natural bevel to either side, creating relief and dimensionality similar to the Augsburg sheath.

Figure 14. Bone tools, possibly used for leatherworking, displayed at the National Museum of Scotland (photo by Wayne Robinson, used under Creative Commons 2.0).

Figure 15. Tooling in process showing primary tools used to produce decoration.

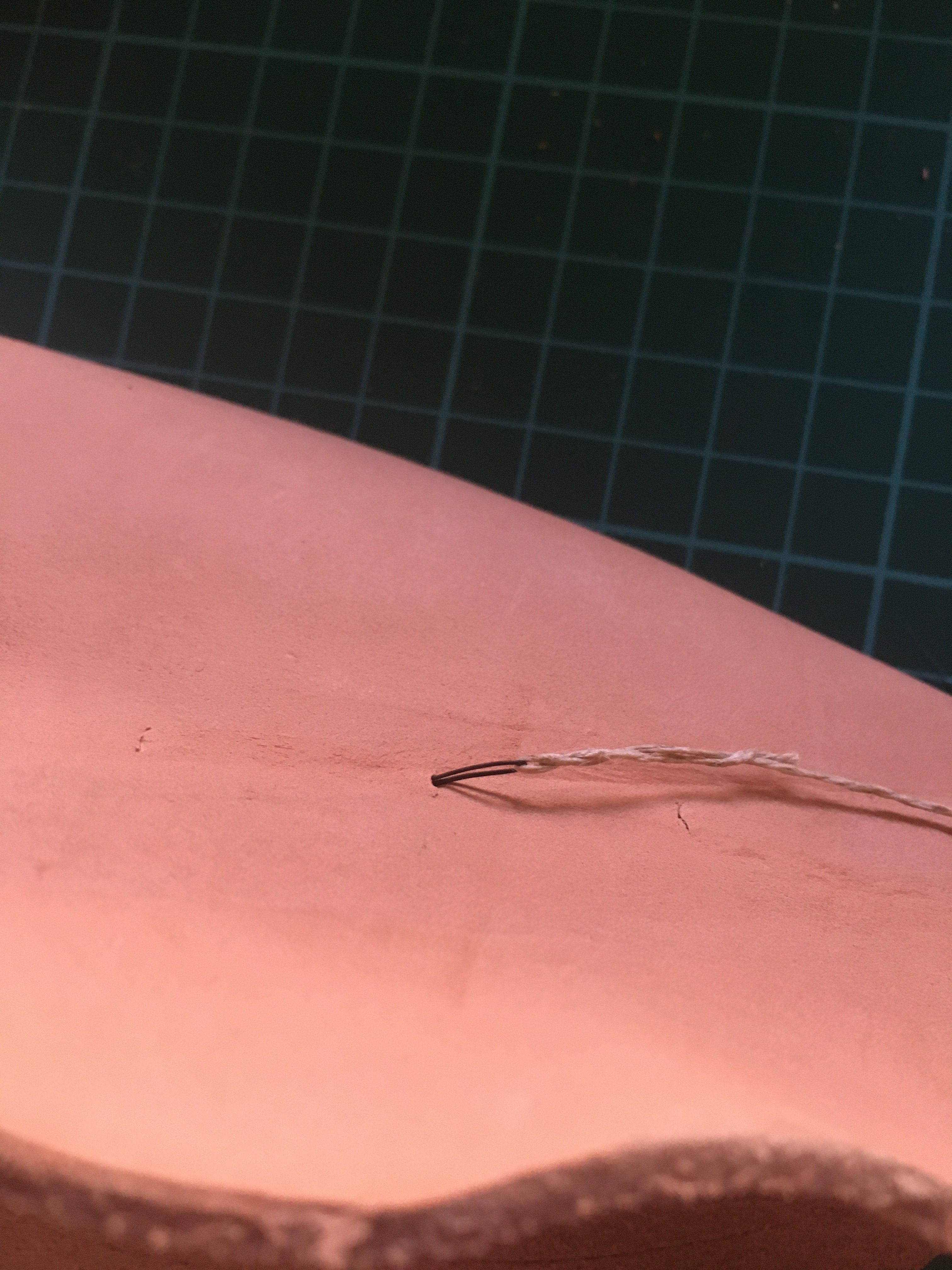

Stitching

Once tooling of the main body was complete, the sheath was sewn together using the modified tunnel stitch technique used on the Groningen sheath (also used for this purpose in Viking-age York.[32] I used the smaller of my two awls (which was sharpened into a slightly flattened-diamond cross section) to punch the holes, going into each one twice from the grain side in opposite directions. With no conclusive proof of what was used to draw the thread through the holes in the 7th century, I experimented with using a large needle as well as a boar’s bristle, a technique documented to at least the 15th century.[33] Both worked well, but when stiffly waxed, the thread actually passed through the stitching holes on its own as well. When the stitching was loosely complete, the core was inserted and the stitching drawn tight to hold it in place. The stitch holes were then burnished closed with a polished bit of bone.

Figure 16. Creating stitching holes (left) and stitching using boar’s bristle, showing approximate 45-degree angle of stitch hole.

Figure 17. Edge closure partially sewn, showing hidden stitching prior to core insertion.

Figure 18. Seam after sewing; left shows stitch holes immediately afterward, right shows holes after light burnishing.

Once the sheath was stitched closed and the core inserted, I trimmed the top edge to the final dimension, cutting through the double-thickness of the leather. I then completed the tooling along the top edge.

Figure 19. Stitching complete, edges trimmed, ready for final tooling around closure edge.

Figure 20. Tooling in progress on upper edge (stitch holes opened up briefly when this part was re-dampened, but I burnished them closed again when I was done).

Figure 21. Leatherwork complete, ready for riveting and finishing with oil and tallow.

Finishing

For finishing, period methods appear to have included oil or tallow, possibly in combination. The Viking-era method cited by Regia Anglorum states that cod oil was used, followed by tallow.[34] Although readily accessible to North Sea cultures, cod oil would not have been produced locally in northern Italy, and I did not find evidence of other fish species used for this purpose in the Italian peninsula or alpine region. I was also unable to document the use of neatsfoot oil as early as the 7th century, but the use of olive oil is recorded in Pliny’s Natural History (15.33-34) as a common 1st century CE Roman method for greasing leather items and shoes. As olives are cultivated in all but the most mountainous parts of the Italian peninsula, this seemed to be a plausible choice. The sheath was wiped down with olive oil, finished with beef tallow, and left undyed; although leather dying techniques were certainly known in period in the Mediterranean sphere, nothing in the sources used to guide this reconstruction note the use of dyed or painted leather in seax sheath construction, so I have chosen to leave the natural color. The oil and tallow darkened the hide significantly, and I expect it to continue to darken over time. To seal the pores and burnish the surface, I used a polished sheep rib – similar tools have been discovered in Neanderthal contexts; known as a lissoir or plisseur, this simple tool is still used by leatherworkers today for burnishing, smoothing, and creasing tasks.[35]

Figure 22. Work in progress, sheep rib burnisher at far right.

Riveting

The large studs were peened from the back side. I was initially skeptical of how well this would work without some sort of washer on the back side, but the mushroomed portion of the rivet actually widens substantially and in test pieces, resisted attempts to pull off the tab with much more force than the connection would actually have been subject to during normal use. The small rivets were clipped to just over the 4mm recorded shank length and were crimped over slightly in opposing directions. My tiny jeweler’s anvil was the only surface I had available, significantly hampering the process. With the hardware and strap holders installed, I applied a final coat of tallow, using it to seal the edges as well, and burnished the raw edges with the sheep rib.

Figure 23. Peening studs to affix strap holders using Barbie-sized anvil.

Lessons learned

This project was the most substantial undertaking of this type that I had ever completed; the research required a deep dive into archaeological reports and other sources written in Italian and German, both of which I read rather slowly, and in Dutch (for which I required some assistance from Google translate). The actual execution also included a lot of “firsts” – the tooling was much more curvilinear than anything I had previously done and required some practice to get the hang of it, and each new aspect of the construction had to be tested first, as both the stitching technique and the installation of the large studs were new to me and needed some experimentation to make sure they would work correctly on the actual sheath. The only prior experience I had with fabricating a wooden core was a sword scabbard produced this past summer but this was not directly transferrable as the scabbard involves several extra textile and leather layers not supported by archaeological evidence for seax sheathes.

While the stitching method worked very well and will be incorporated in many future projects, I would likely use a different means of forming the core – either using hand-split lath or possibly steam-bending thin wooden strips around the blade. The method I used this time produced a successful result, but it required an annoying amount of material removal to reduce the half-inch-thick boards to the approximate quarter-inch end thickness. Ensuring that the two halves were properly registered to one another was also a hassle but could be remedied by using the two unsmoothed pieces of a hand-split piece of wood face-to-face. The use of green wood might have offered some advantages but would have required much more time for the piece to dry after forming. The concept of the core itself does provide several functional benefits, in particular removing some of the more extreme stress out of the portion of the sheath leather that wraps around the transition from blade to grip and acting as a natural stop when the blade is inserted. It would also explain why the Augsburg example does not show significant wear or major stretching at that transitional point. Stretching at that point would also distort any tooling, and eliminating the issue allows for a consistent design motif down the length of the sheath without having to compartmentalize the design elements for the handle and blade sections.

The strap configuration for the suspension currently consists of two thongs passed through the holders and doubled back (version at far left, Fig. 24). Another possible method might involve running a strap through the holder and back up around the front of the sheath, or even using a strap with a wider tab at the bottom to act as a stop. I expect to continue to experiment with this to see what feels most comfortable and practical.

Figure 24. Cross section showing potential suspension thong configurations to test.

Figure 25. The completed sheath.

Bibliography

Carlson, Mark. “Leatherworking of the Middle Ages – Threads in Sewing Leather.” Accessed February 25, 2020. http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/leather/thread.html.

Diaconus, Paulus. Pauli Historia Langobardorum: In Usum Scholarum Ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Recusa. impensis bibliopolii Hahiani, 1878.

Gregory of Tours. History of the Franks. Translated by Ernest Brehaut. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916. http://archive.org/details/historyoffranks00greguoft.

Grömer, Karina, Gabriela Ruß-Popa, and Konstantina Saliari. “Products of Animal Skin from Antiquity to the Medieval Period.” Annalen Des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien, Serie A 119 (January 1, 2017): 69–93.

Lane, Alan, and Mark Redknap. Llangorse Crannog: The Excavation of an Early Medieval Royal Site in the Kingdom of Brycheiniog. Oxbow Books, 2020.

McComb, Isobel P. “A Technological Study of Selected Osseous Artifacts from the Upper Paleolithic of Britain and Belgium.” Ph.D thesis, Jesus College, Oxford University, 1988. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bec9/f5c00fcb1f641d5d7342a0825522a7869076.pdf.

Mould, Quita, Ian Carlisle, and Esther Anita Cameron. Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York. Council for British Archaeology, 2003.

Paroli, Lidia. “The Langobardic Finds and the Archaeology of Central Italy.” In From Attila to Charlemagne: Arts of the Early Medieval Period in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, N.Y.: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

“Regia Anglorum – Anglo-Saxon and Viking Crafts – Leatherwork.” Accessed February 25, 2020. https://regia.org/research/life/leatwork.htm.

Rigoni, Marisa, and Annachiara Bruttomesso. Materiali di età longobarda nel Museo “G. Zannato” di Montecchio Maggiore. 1. La necropoli dell’Ospedale di Montecchio Maggiore. All’Insegna del Giglio, 2011.

Roffia, Elisabetta. La necropoli longobarda di Trezzo sull’Adda. All’Insegna del Giglio, 1986.

Rupp, Cornelia Babette. Das langobardische Gräberfeld von Nocera Umbra. All’Insegna del Giglio, 2005.

Salin, Bernhard, and J. (Johanna) Mestorf. Die altgermanische Thierornamentik : typologische Studie über germanische Metallgegenstände aus dem IV. bis IX. Jahrhundert, nebst einer Studie über irische Ornamentik. Stockholm : K.L. Beckmans büchdruckerei, in Kommission bei A. Asher, Berlin, 1904. http://archive.org/details/diealtgermanisch00saliuoft.

Soressi, Marie, Shannon Mcpherron, Michel Lenoir, Tamara Dogandzic, Paul Goldberg, Zenobia Jacobs, Yolaine Maigrot, et al. “Neandertals Made the First Specialized Bone Tools in Europe.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (August 12, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1302730110.

Ulrich, Roger B. Roman Woodworking. Yale University Press, 2007.

Werner, Joachim. Die Ausgrabungen in St. Ulrich und Afra in Augsburg, 1961-1968. C.H. Beck Verlag, 1977.

Ypey, Jaap. “Twee Saxscheden Uit Noord-Nederland.” Groningse Volksalmanak, 1979 1978, 213–27.

[1] Lidia Paroli, “The Langobardic Finds and the Archaeology of Central Italy,” in From Attila to Charlemagne: Arts of the Early Medieval Period in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 143–44.

[2] Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, trans. Ernest Brehaut (New York: Columbia University Press, 1916), IV, http://archive.org/details/historyoffranks00greguoft.

[3] Marisa Rigoni and Annachiara Bruttomesso, Materiali di età longobarda nel Museo “G. Zannato” di Montecchio Maggiore. 1. La necropoli dell’Ospedale di Montecchio Maggiore (All’Insegna del Giglio, 2011), 51.

[4] Elisabetta Roffia, La necropoli longobarda di Trezzo sull’Adda (All’Insegna del Giglio, 1986), 69; Jaap Ypey, “Twee Saxscheden Uit Noord-Nederland,” Groningse Volksalmanak, 1979 1978, 216; Joachim Werner, Die Ausgrabungen in St. Ulrich und Afra in Augsburg, 1961-1968 (C.H. Beck Verlag, 1977).

[5] Rigoni and Bruttomesso, Materiali di età longobarda nel Museo “G. Zannato” di Montecchio Maggiore. 1. La necropoli dell’Ospedale di Montecchio Maggiore, 31.

[6] Rigoni and Bruttomesso, 31.

[7] Rigoni and Bruttomesso, 40.

[8] From Montecchio Maggiore via Verona, Augsburg (Augusta Vindelicorum) was directly north along the Via Claudia Augusta through the Brenner Pass.

[9] Werner, Die Ausgrabungen in St. Ulrich und Afra in Augsburg, 1961-1968.

[10] Quita Mould, Ian Carlisle, and Esther Anita Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York (Council for British Archaeology, 2003), 3263.

[11] Ypey, “Twee Saxscheden Uit Noord-Nederland,” 217.

[12] Ypey, 213.

[13] Mould, Carlisle, and Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life, 3263–64.

[14] Ypey, “Twee Saxscheden Uit Noord-Nederland,” 213.

[15] Roffia, La necropoli longobarda di Trezzo sull’Adda, 91.

[16] Mould, Carlisle, and Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life, 3380.

[17] Karina Grömer, Gabriela Ruß-Popa, and Konstantina Saliari, “Products of Animal Skin from Antiquity to the Medieval Period,” Annalen Des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien, Serie A 119 (January 1, 2017): 72.

[18] Mould, Carlisle, and Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life, 3259–61.

[19] Paulus Diaconus notes that the Langobards had garments of linen at this time. Paulus Diaconus, Pauli Historia Langobardorum: In Usum Scholarum Ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicis Recusa (impensis bibliopolii Hahiani, 1878), IV, 22.

[20] Rigoni and Bruttomesso, Materiali di età longobarda nel Museo “G. Zannato” di Montecchio Maggiore. 1. La necropoli dell’Ospedale di Montecchio Maggiore, 52.

[21] Werner, Die Ausgrabungen in St. Ulrich und Afra in Augsburg, 1961-1968, 176.

[22] Roffia, La necropoli longobarda di Trezzo sull’Adda, 52.

[23] Roffia, 92.

[24] Cornelia Babette Rupp, Das langobardische Gräberfeld von Nocera Umbra (All’Insegna del Giglio, 2005), 96.

[25] Roffia, La necropoli longobarda di Trezzo sull’Adda, 261.

[26] Ypey, “Twee Saxscheden Uit Noord-Nederland,” 217.

[27] Bernhard Salin and J. (Johanna) Mestorf, Die altgermanische Thierornamentik : typologische Studie über germanische Metallgegenstände aus dem IV. bis IX. Jahrhundert, nebst einer Studie über irische Ornamentik (Stockholm : K.L. Beckmans büchdruckerei, in Kommission bei A. Asher, Berlin, 1904), 245–46, http://archive.org/details/diealtgermanisch00saliuoft.

[28] Mould, Carlisle, and Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life, 3382–83.

[29] Roger B. Ulrich, Roman Woodworking (Yale University Press, 2007), 13, 21, 27.

[30] Mould, Carlisle, and Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life, 3237.

[31] Alan Lane and Mark Redknap, Llangorse Crannog: The Excavation of an Early Medieval Royal Site in the Kingdom of Brycheiniog (Oxbow Books, 2020), 272.

[32] Mould, Carlisle, and Cameron, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life, 3261.

[33] Mark Carlson, “Leatherworking of the Middle Ages – Threads in Sewing Leather,” accessed February 25, 2020, http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/leather/thread.html.

[34] “Regia Anglorum – Anglo-Saxon and Viking Crafts – Leatherwork,” accessed February 25, 2020, https://regia.org/research/life/leatwork.htm.

[35] Marie Soressi et al., “Neandertals Made the First Specialized Bone Tools in Europe,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (August 12, 2013): 4, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1302730110; Isobel P. McComb, “A Technological Study of Selected Osseous Artifacts from the Upper Paleolithic of Britain and Belgium” (Ph.D thesis, Oxford, England, Jesus College, Oxford University, 1988), 250–51, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bec9/f5c00fcb1f641d5d7342a0825522a7869076.pdf.