An investigation of decorative woven leatherwork techniques from wallet fragments found at Birka

Introduction

Not long ago, I decided to make a coin purse loosely based on the well-known and oft-reproduced wallet found in Grave 750 at Birka (Bj. 750), the best-preserved example of a group of small leather items adorned with minute strips of gilded leather woven into decorative patterns. Although mine was not intended as a replica of the original, the goal was to use the same decorative techniques and basic design to create a personalized version to be given as a gift. In the process, I encountered a number of inconsistencies between photographs of the original and the published drawings and museum reconstructions (which have in turn served as the basis for more replicas).

I had initially used the reconstruction drawing in Holger Arbman’s Birka I (the original publication of the Birka finds) as my model, which appears to depict the technique used in most modern reproductions, including several museum replicas. Closer examination of photographs of the extant fragments suggested a different method than the one shown in the drawing, and in looking at comparisons with other similar items found at Birka, the same issue cropped up: the most common way of reproducing the decorative motif today does not seem to have been the method used on the originals. As I had already invested a substantial amount of time in the more common method, it was my hope that there were perhaps coexisting techniques in evidence at Birka, including the one I first used. Alas, it was not to be.

My present contention is that the c.1940 drawing of Harald Faith-Ell’s reconstruction of the Bj. 750 purse published in Birka I utilized some artistic shorthand in its rendering of the decoration. This somewhat misleading (if inadvertently so) depiction was then faithfully copied and has spawned a host of replicas (of both the Bj. 750 purse and other objects with similar decoration) that do not use the technique found on the originals.

A close inspection of photographs, bolstered by the verbal descriptions of the originals, seems to contradict what I term the “basketweave” technique now used in many reproductions of these small leather finds, and I was actually unable to discern any evidence of this technique among the various leather fragments at Birka. To that end, this paper will address the following questions:

- What techniques were actually used on the original pieces?

- Do they differ from the numerous reconstructions and if so, how?

- What are the most reliable sources to identify the correct technique?

Although the original focus was the coin purse from Bj. 750, as it is one of the best-preserved and most widely replicated of the small leather goods excavated at Birka, I broadened my scope to include fragments from six other graves at Birka that incorporate the same type of decoration. As a result, the discussion that follows can be applied more broadly to the reproduction of this style of leather decoration.

Anyone wishing to faithfully reproduce this technique or one of these objects faces several obstacles. At present, the best-quality photo- graphs of the extant finds are nearly 90 years old and, although freely available online, are presented as plates in a separate volume from the accompanying explanatory text, which itself contains little analysis of the body of examples as a whole. That analysis was published more than forty years later, but is accompanied only by a line drawing rather than with detailed photographs of the decorative technique. To compound the issue, both publications are in German; I have quoted the relevant excerpts in English, and in the Appendix, I provide a full translation of Anne-Sofie Gräslund’s discussion of the wallets featuring woven deco- ration, excerpted from her the chapter on leather bags and purses originally published in Birka II:1.

So rather than denigrate the efforts of the numerous craftspeople who have painstakingly produced replicas of the Bj. 750 wallet, my aim here is simply to compile as much evidence as possible in one place and let the reader arrive at their own conclusion as to how they wish to reconstruct the pieces that utilize this type of decoration. The section below will summarize the most prominent reconstructions, noting where they seem to diverge from the extant fragments. The following section will provide a more detailed survey of the photographic evidence from Bj. 750 and similar finds from other graves excavated at Birka. I will then reference written descriptions by scholars who have handled the materials personally, and the final section will present several test panels to demonstrate a method that yields results consistent with the original leather finds and offers other advantages over the more common method in regard to both ease of construction and durability.

Prior Reconstructions

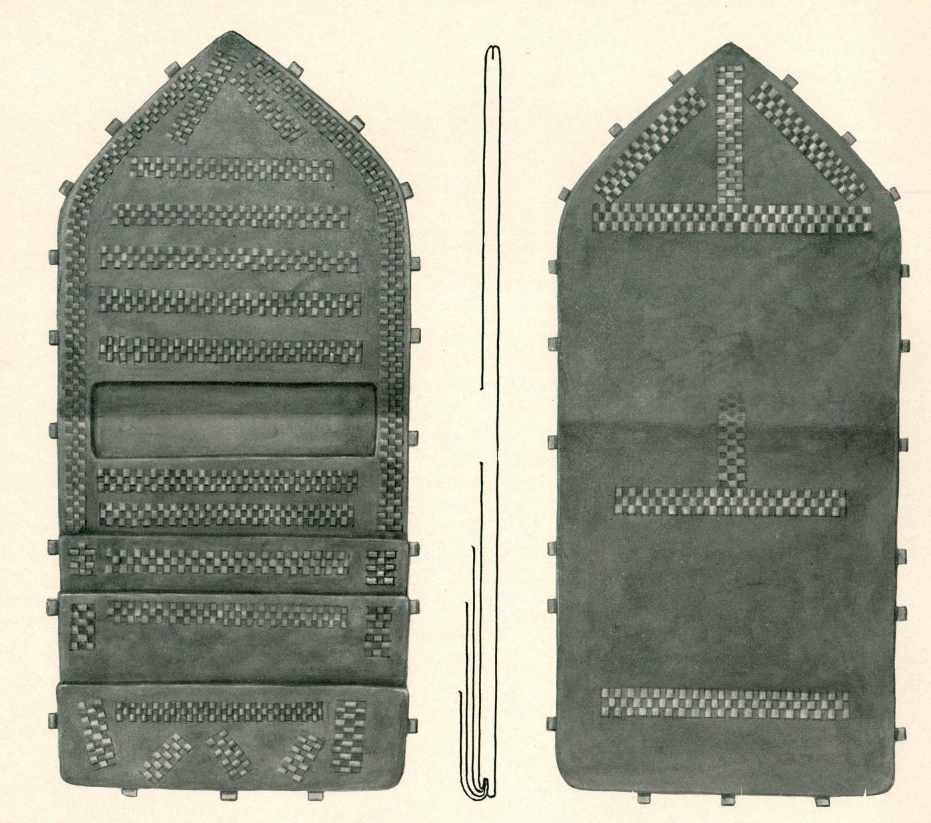

The reconstruction drawing published in Birka I (see Fig. 1) is one of the most readily accessible online examples available to someone seeking to replicate this type of object. The illustration also seems to be the basis for most of the physical reconstructions that followed; I suspect that it is the ‘face that launched a thousand ships.’ Unfortunately, the image shows several details that do not seem to be based on the actual purse fragments.

The basic decorative element repeated across the surface of the purse – and found on more than a dozen other similar objects at Birka – comprises three parallel strips of gilded leather drawn through slits cut in the main body. At first glance, the illustration seems to be a clearer depiction of a technique rendered difficult to see in photographs of the crumpled leather of the purse. Examining the illustration closely (see Fig. 2), one can quite easily discern continuous horizontal lines that span the width of each decorative stripe, implying a continuous slit through which all three strips are drawn in an alternating fashion. The image also presents an extremely regular checkerboard pattern throughout each stripe and shows no gap between the parallel strips.

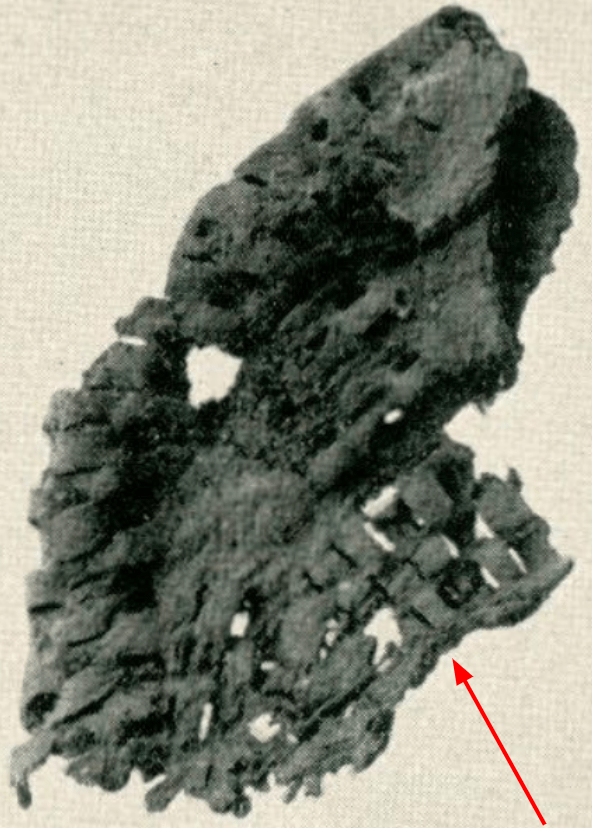

When compared to the photographs of the actual piece, these details seem to be a matter of artistic convenience rather than a careful depiction of the object itself. In examining a photograph of the same corner of the piece taken in the 1930s and published in the same volume (see Fig. 3), the continuous perpendicular horizontal lines are noticeably absent; while this could be attributed to the warping of the leather surface as it conforms to the woven thongs in this area, examination of the photograph did not show this detail anywhere. Secondly, the photographs show that the individual thongs are separated by a small gap – perhaps a millimeter wide – and are not as closely spaced as the drawing indicates. Again, this could be attributed to shrinkage (if the gilded strips shrank at a different rate than the surrounding material), but if that were the case, one would expect to see gaps on either side of the strips.

Having noted the problematic aspects of the reconstruction drawing, I turn to the two prominent replicas of the Bj. 750 purse currently on display in museums in Sweden. The replicas displayed at the Historiska Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, and in the museum at Birka in fact appear virtually identical and seem to be based on the original reconstruction drawing (see Figs. 5 and 6). Both show the highly regular woven pattern and closely- spaced gilded thongs precisely as depicted in the reconstruction drawing. Both also utilize what I referred to earlier as the “basketweave” technique (see Fig. 4); to create each decorative stripe, a series of parallel slits are cut wide enough to accommodate all three of the gilded thongs, which are then woven through these continuous slits in an alternating fashion – similar to a tabby-weave fabric or a pie-crust lattice.

This can be clearly seen in Fig. 5 (below), which shows the reverse side of the front panel of the purse. The areas of overlap (indicated by black arrows) are formed where the gilded strips are visible on the front side; in keeping the front side flat, the craftsperson forces the main purse material to stretch below. The perfect alignment of the checkerboard pattern is most easily achieved through this method, since weaving errors are immediately apparent and the strips are naturally pressed close together. While this creates an appearance that is satisfying to the modern eye, it does not seem to conform to the appearance of surviving areas of decorated purse fragments. The following sections will provide additional photographic evidence of both the Bj. 750 fragments and finds from several other graves that demonstrate the same decorative technique.

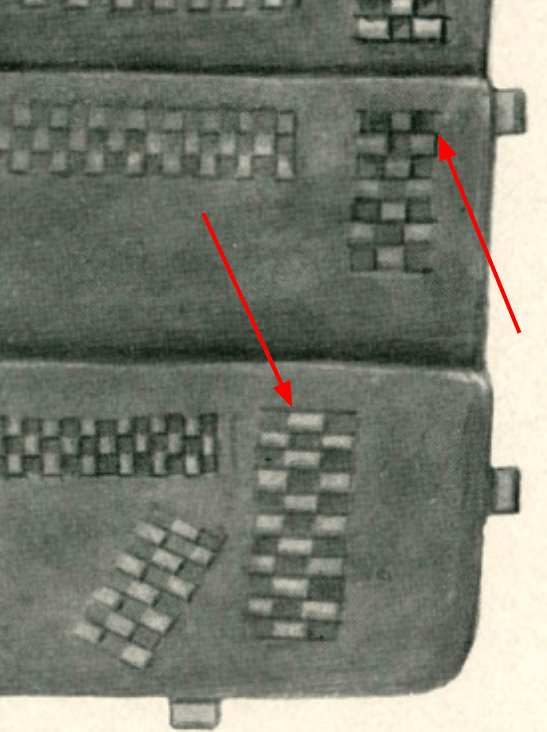

Returning to the photographs of the original piece, I began to look for additional details. The basketweave method clearly produced a result consistent with the drawing, but did not seem to represent the alignment and wear patterns visible in several of the published photographs. Upon closer inspection of a recent photograph taken at the Historiska Museet, a fragment of one of the lower pockets offered a useful bit of information. On this piece (the upper right corner of the second-lowest pocket, the same area shown in Fig. 3), the middle strand of gilded leather has been lost and the holes are clearly visible (see Fig. 7). While most other areas of decoration are fairly consistently spaced, in the detail at left, the incisions for the middle strip are actually slightly offset from those on either side.

This offset would be impossible to achieve using a continuous slit, and indicates that the gilded strips were each drawn through an individual slit. These slits would be closely spaced, but not close enough to tear across the intervening space – thus creating the small gap between the parallel strips. Although the more carefully aligned areas of decoration on the purse might give the illusion of a continuous horizontal line across the full width of the decorative stripe, some degree of offset between adjacent rows of slits would produce the slight irregularities visible on several of the fragments of the Bj. 750 wallet.

At this point, the evidence strongly indicated that at least some portion of the wallet was decorated using a technique other than the “basketweave” method – instead of a single long slit for all three strips, the purse fragments displayed three parallel rows of small slits each accommodated a single gilded strip (see Fig. 8). To determine whether this individual-slit method was the sole method or whether the two methods coexisted among the Birka finds, I examined additional finds of similar decorated leather goods published in Birka I.

Comparison of Similar Fragments

In addition to the more intact wallet in Bj. 750, the publication included photographs of the surviving portion of a second, similar purse found in Bj. 750 as well as fragments of small leather items – wallets, pouches, etc. – from six other graves, all of which featured this type of decoration (I excluded any fragments that were too degraded for me to determine whether the slits were for seams or decorative lacing). These objects were found in the following graves: Bj. 904, 543, 837, 717, 709, and 1074.

The examples in Bj. 904 and 543 are definitively identified as wallets (Gräslund, 144) while those in Bj. 837, 709 and 717 are identified in Birka I as fragments of a leather bag or pouch; Bj. 1074 contained a bone comb in a leather carrying case with a suspension loop at one end, and both sides of the comb case were decorated using the same technique.

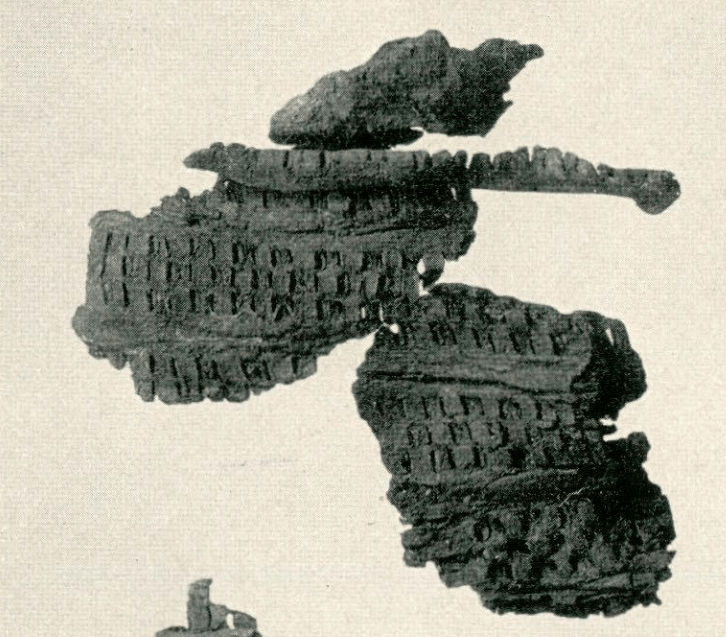

Although the second purse or wallet from Bj. 750 is too fragmentary to reconstruct, the surviving piece was quite well preserved at the time it was photographed for initial publication (see Fig. 9). In this image, the spacing of the parallel strips is much wider than what would be achieved using the basketweave method. In addition, the alignment of the pattern also shows that the slits are not continuous. Of particular interest is the middle row of decoration, where the maker was either unconcerned with creating a regularly alternating checkerboard pattern or deliberately intended to align the visible portion of the center strip in the same pattern as the two outer strips. Either way, the result is that the gilded squares are directly next to one another and clearly separated by a narrow margin, thus leaving no doubt that the strips were drawn through individual slits.

With the exception of the purses in Bj. 750 and 543, the majority of the remaining fragments have lost most (if not all) of the decorative strips, which actually makes it easier to discern how the strips were applied. In each of the following instances, examination of the photographs showed clear evidence of multiple, parallel rows of tiny slits. Only one portion of one of the six fragments of the purse from Bj. 904 (see upper fragment, Fig. 10) seemed slightly ambiguous, but the continuity of the slits (indicated by yellow arrow) may be the result of stretching/tearing or general degradation of the margin between rows of slits; other portions of the same row appear to retain this margin (indicated by red arrow). The remainder of the fragments clearly show separate slits for each strip, and in the lower fragment in Fig. 10, a more extreme offset can be seen as well. A third fragment of the Bj. 904 wallet also shows separate slits and the reconstruction drawing (see Fig. 11) is also unambiguous; the parallel rows of individual slits are depicted throughout.

An extremely clear example of the technique can be seen in the fragment from Bj. 709. Although Arbman described the remnants as too rotten to reconstruct, the object was almost certainly some type of purse or wallet, and contained a lead weight, a lump of bronze, and a coin (Arbman, 244). The surviving fragments display a decorative motif very similar to the wallets from Bj. 750 made up of bands comprising three parallel strands of decorative lacing, and the image in Fig. 13 clearly depicts the neatly-aligned rows of tiny incisions for individual strips.

Another fragment from Bj. 717 also shows indisputable evidence of the individual slit method. Although the margins between strips are quite narrow, they are quite distinct in the photograph (see Fig. 14). Although Arbman was initially uncertain whether the absent decorative elements were leather strips or fabric/thread (Arbman, 250), no explanation is provided for his speculation that they would be anything other than leather, and this commentary does not appear in the descriptions of the other similar leather goods in the publication. While it is certainly possible that fiber-based strips could be used for this purpose, the deformation around many of the slits on the fragment from Bj. 717 suggests that whatever was used would have been roughly the same size as the gilded strips found on other examples.

The final example in this brief survey is the comb case from Bj. 1074 (Fig. 15). The comb case appears to have been executed with slightly less minute accuracy than many of the purses, and the impressions made by the decorative stripsare somewhat narrower in relation to the slits – whether this reflects the makers intent or is the result of degradation after burial is unclear. In this example, the upper half displays wider margins between the adjacent strips – exceeding 50% of the width of the slits in some areas, although still reasonably well aligned to form the checkerboard pattern. The margins between strips clearly show that individual slits were used for each strip.

Textual Descriptions of Technique

One of the greatest challenges in under- standing the way these purses were made is the inability to handle and examine the extant fragments. The photographs in Birka I are among the best available online (even the highest resolution images in the Swedish Historical Museum database are not sufficiently detailed). Rather than rely solely on scrutiny of a photograph in my attempt to disprove a pervasive interpretation, I turned to the descriptions of the leather objects written by Holger Arbman and Anne-Sofie Gräslund, both of whom had access to the physical objects – Arbman in the 1930s and Gräslund some forty-odd years later. This chronological gap is relevant as Gräslund notes that the Bj. 750 wallet had deteriorated noticeably since it was originally photographed in the 1930s (Gräslund, 142) – thus the images from Birka I are likely to show more of the original material than more recent photographs.

In Birka I, Arbman describes the more intact Bj. 750 wallet as follows:

At the corner of the chamber lay a second leather pouch rolled up, about 20 cm long and 10-11 cm wide, only about half preserved, the pouch consists of a piece of leather on which five other pieces are sewn as compartments in such a way that that one compartment is on one side of the center, four are on the other side, both parts decorated with gilded leather straps drawn through rows of cuts, around the edge small gilded leather eyelets.

(Arbman, 271)

Although Arbman’s description of the comb case in Bj. 1074 is slightly more specific, the description of the wallet in Bj. 750 is quite vague. He notes that the comb case had two decorative stripes on each side, and that each stripe was made up of “three rows of small cuts for very thin and originally gilded (?) leather straps (Arbman, 447).” Yet Arbman does not describe the decoration method of the Bj. 750 wallet in any greater detail beyond ‘straps drawn through rows of cuts.’ What constitutes one ‘row?’ How large were the cuts?

In subsequent studies of the Birka materials, Gräslund provides a bit more detail. She notes that at least 15 other leather objects utilized the same method; these include the additional items from Birka I shown in the previous section. In Gräslund’s study of the various leather bags and purses found at Birka, the materials were grouped into three general types – the wallet, the lyre purse, and bags with folding flaps covered in metal fittings (frequently referred to elsewhere using the Magyar term ‘tarsoly’). The purses from Bj. 750 and Bj. 904 are mentioned as the best-preserved examples of the wallet type, but she notes that numerous other fragments display “the characteristic decoration with incisions and gilded leather stripes” and are possibly examples of the wallet type as well (Gräslund, 144, see Appendix).

While she does not provide this level of detail for the other purse fragments, Gräslund describes the fragments of both purses from Bj. 750 in the same fashion (italics are mine): one has “triple rows of small incisions on the inside and on the outside, the gold-plated leather strips pulled through so that a kind of checkerboard pattern arises” (Gräslund, 143) and the other is described as “decorated with four groups of incisions of three rows each with drawn-in, gilded strips (Gräslund, 144).”

This textual description provides incontrovertible evidence for the individual-slit method for the Bj. 750 items. Of particular interest to me was the fact that Gräslund does not describe any other method of executing this type of motif on these or any other items, nor do any photographs of the other purse fragments suggest it. It is impossible to say with any certainty whether the current prevalence of the basketweave method stems directly from the museum reconstructions or if modern craftspeople arrived at it spontaneously from either the original drawing or poor-quality photographs of the fragments online; the basketweave method may seem like a fairly obvious solution to anyone possessed of a smallish chisel. Nevertheless, an examination of the Birka ‘wallet’ purses (and comb case in Bj. 1074) did not seem to yield any evidence that a continuous-slit method was practiced at Birka for this type of leather decoration.

Proof of concept

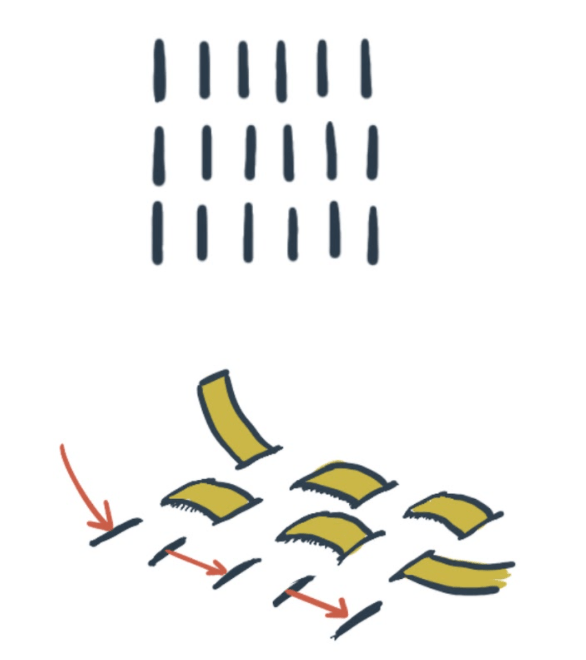

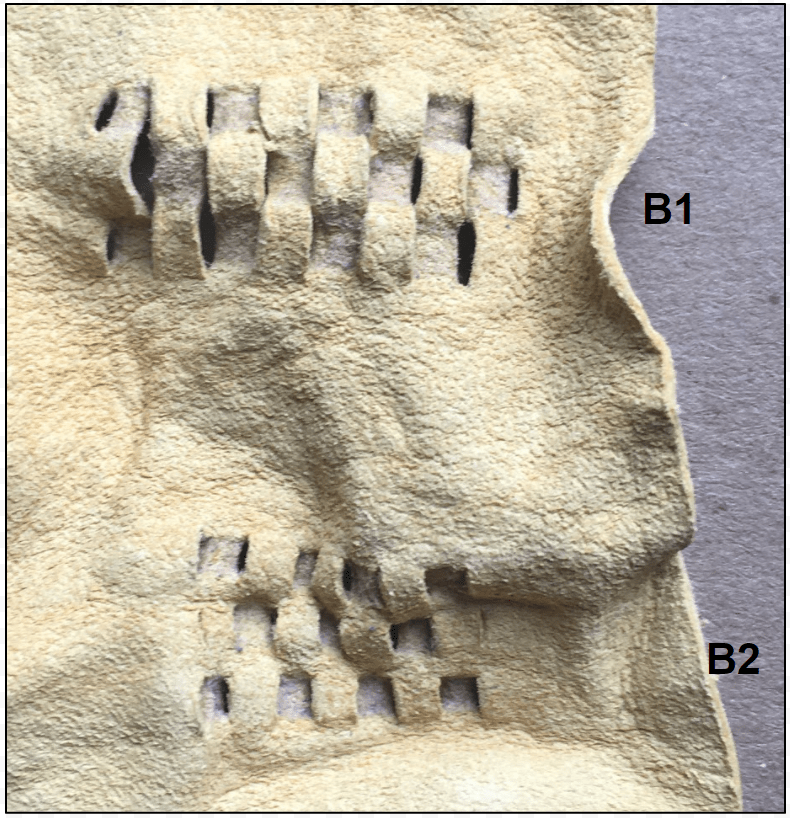

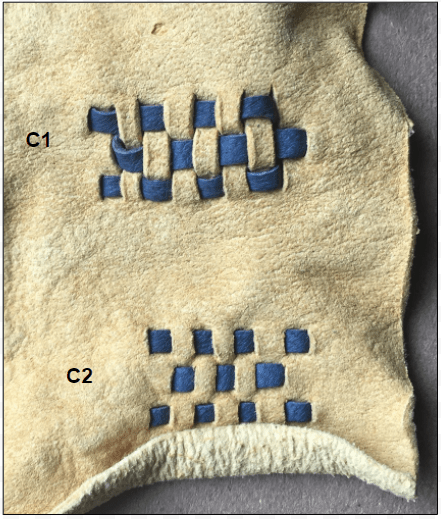

Having already made one purse predicated on erroneous assumptions, I decided to engage in a bit of experimentation to compare the two techniques – the modern basketweave approach and the individual-slit method, which I now believe to be the historical technique – and see what else I might learn about how the two methods behave during fabrication and how they respond to wear-and-tear. I produced three test panels, each showing both decorative methods with a 7-row repeat (2-3cm segment) of the decorative motif. Test panels demonstrate the basketweave tech- nique (labeled as A1, B1, and C1 in subsequent images) alongside the individual slit technique (labeled as A2, B2, and C2). Samples of both techniques were then subjected to simulated light wear and moisture and were then compared to photographs of extant pieces.

I present the test panels here merely as proof- of-concept of the technique rather than a finished object meant to replicate an original. The original purse was made using an alum-tawed bovine leather (Gräslund, 142), which would have been naturally soft and quite stretchy and flexible (Vest, 68). The test panels used sheep hide tanned with pure fish oil; although not the same material, this leather provides a reasonable approximation of the stretchiness of the alum-tawed leather and reacts equally poorly to soaking (alum-tawed leather is not stable in water [Vest, 68]). The decorative strips on most of the extant examples were covered with gold leaf, but for illustrative purposes here, the gold leaf was unnecessary. Instead, the thongs are cut from a thin scrap of dyed goatskin for best contrast in photographs (see Fig. 16).

The continuous slits for the basketweave samples were cut with a ½” chisel, while the individual- slit samples were pierced using a 3mm diamond awl similar in size and cross-section to one found in an Anglo-Scandinavian context in York, England (see #2722 in particular in Figure 17).

Panel A served as a control while Panels B and C were saturated, patted to remove excess water, squished a bit, and then left carelessly to dry overnight. Panel B then had the decorative strips removed to show the deformation around the slits. Comparison between the test panels and the images from Birka I leaves little doubt in my mind that the individual-slit panels best match the fragments of the various leather items found at Birka, both in the appearance of the intact decoration and in the marks that remain when the gilded strips have been lost. Figures 18 through 21 show the dampened and dried test panels alongside details of extant fragments.

Rather than belabor the point about which method I believe is “correct” or most historically accurate, in the spirit of experimental archaeology I will instead offer some observations based on the fabrication and examination of the test panels that may be of interest to others.

Strength: The basketweave test panels deformed much more than I would have expected, although in retrospect this should not be surprising – this method creates long thin ‘warp’ strips that are placed under pressure from opposing directions by the decorative lacing ‘weft.’ Tugging on an unsoaked test panel at a diagonal to the woven strip causes the slits to gape, particularly at the ends of the decorative stripes. The ‘warp’ strips of the main body also stretched noticeably when the test panels were dampened and handled. In contrast, the single-slit method retains a stronger matrix beneath the decorative motif and does not weaken the surface of the main leather nearly as much. In fact, the same diagonal stretch test found that the decorative stripe was actually slightly more rigid than the surrounding leather, raising the intriguing possibility (admittedly obvious in hindsight) that this decorative method might have also served a structural purpose, adding strength to an otherwise delicate leather item and reducing deformation due to use. The basketweave method does not offer this advantage, and on some leathers may actually make for a less durable end product.

Ease of construction: The individual slit method solves several of the problems caused by the basketweave method. The basketweave technique becomes a bit difficult on the third and final strip – to ensure a neat, gap-free appearance, the slits should be fairly tight by the time the final strip is woven through, and accomplishing this without tearing the main body leather can require some patience. Using individual slits eliminates this problem, as the slit can stretch as needed to accommodate the strip – this provides a bit of leeway without the risk of tearing through the margin between the strips. I soon found that a moderately stretchy leather was quite forgiving in this regard; although I was more conservative with the earlier test panels, I discovered that I was able to leave very narrow margins without tearing through during the lacing process.

Finishing: Another problem had to do with how to finish the ends. As noted, the individual slits result in greater rigidity, and as each slit can be cut to fit the strip snugly, the system also creates sufficient friction to hold each contrasting strip firmly in place without the need to anchor it with knots, tabs, or stitching. Although the fragment from Bj. 543 is too deteriorated to draw any firm conclusions, the strips do not appear to be tabbed or otherwise anchored to one another on the back side of the panel, and seem to be left slightly overlong without knots or other finishing (see Fig. 22).

Conclusion

Although the basketweave version is prevalent and has been propagating across Pinterest for some time, all available photographic and written evidence supports the individual slit method as the historical technique used to produce the artifacts found in Birka. The only basis for the basketweave technique seems to be a misinterpretation of the first published reconstruction drawing from 1940, which has circulated widely in recent years. Between the original publication of Birka I and the subsequent analysis published in Birka II:1, the surviving fragments continued to deteriorate and some of the leather finds were lost completely. In my opinion, therefore, the photographic plates in Birka I likely represent the best visual source for further study on the topic. Experimentation indicates that the historical method visible in these early photographs and described in Anne-Sofie Gräslund’s detailed description offers several advantages over the more common modern reproduction technique, and my hope is that this paper will encourage others to try it.

References

Arbman, Holger. Birka I: die Gräber [Text und Tafeln]. Stockholm, Sweden: Almquist & Wiksell Internat., 1940/1943.

Gräslund, Anne-Sofie. “Beutel und Taschen.” Birka II:1; Systematische Analysen der Gräberfunde, edited by Greta Arwidsson, Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, 1986, 141-154.

Mould, Quita, Ian Carlisle, Esther A. Cameron, and R.A. Hall. The Archaeology of York: Vol. 17, Fasc. 16; Craft, industry and everyday life: leather and leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York. York: Published for York Archaeological Trust by the Council for British Archaeology, 2003.

Vest, Marie. “White tawed leather – aspects of conservation.” 9th International Congress of Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Archiv-, Bibliotheks- und Graphikrestauratoren (IADA), Copenhagen, August 15-21, 1999, 67-72.

Appendix

The following is a translation from the original German text of the relevant excerpt from Anne-Sofie Gräslund’s chapter on leather bags and purses (Birka II:1, pp. 143-144)

This bag type consists of a wallet-like case with several compartments, decorated with drawn-in, usually gold-plated leather strips. There are several relatively well-preserved examples of this type, the best from Bj. 750 (2 examples) and 904, according to which the reconstructions (plates 130, 132) are made. The best preserved bag from Bj. 750 has disintegrated starkly since it was photographed in the thirties. It is smooth on the outside and has various compartments on the inside, one large compartment running the entire length of the bag and three smaller ones in descending order of size. Along the outside edge of the bag at different distances there are small, protruding, folded strap eyelets that are gilded. They are sewn (riveted?) to the edge and do not extend into the pocket. The eyelets are approx. 0.7 cm long and about 0.5 cm wide. It is questionable whether it has a function or whether they were only used for jewelry, which seems more believable to me. On one piece from the lower edge you can distinguish four layers of leather, all with folded edges with seam holes. The fifth layer (see the profile, plate 130) would then be the outside or back of the bag, which is also provided with an inwardly folded edge with seam holes. Here it has probably been worked with the aforementioned hidden seam.

The bag is provided with triple rows of small incisions on the inside and on the outside, the gold-plated leather strips pulled through so that a kind of checkerboard pattern arises. The gilding consists of very thin gold leaf. According to Arbman, the bag was folded up in the grave, and on the undecorated part of the fragment at the top right of Plate 131 (which is now kept with the more complete Bag 1) you can see clear imprints of the golden diamond pattern, which must therefore come from the striped decoration on the inside. This fragment could perhaps have belonged to Bag 2 (see below), but since both are of the same type, you can still use these prints to get an idea of how the bag could have been folded.

An interesting observation about the manufacturing technique is that the hem at the end of one of the compartments consists of a folded edge with incisions, whereby the leather strip was pulled through double layers, which never seems to be the case with folded edges with seam holes.

The second bag in Bj. 750 is, as I said, of the same type, but here only a fragment of the middle piece has been preserved. It consists of two layers of leather, the inner of which is decorated with four groups of incisions of three rows each with drawn-in, gilded strips, as described above. The outside is undecorated. Both sides have edges folded against each other, between which a gold-plated strap rose protrudes at one point.

The pouches in Bj. 904 and 543 also belong to the wallet type without a doubt. The latter has a print of gold stripes on the undecorated side (plate 133b), which could indicate that it was folded up. Furthermore I count among this group – with express reservation because of the extremely fragmentary character of the leather – all fragments that have the characteristic decoration with incisions and gilded leather stripes. The following graves contain leather fragments, which may therefore be remnants of wallet-type bags: Bj. 523, 709, 710, 715, 717, 746, 804, 837, 845, 956, 965, 1037, 1149: this also applies to the graves mentioned in Birka 1 with leather fragments with incisions, which fragments have meanwhile been lost: Bj. 503, 724, 731, 834. The leather fragments from Bj. 727, 776 and 808, which have no incisions, but have gilded leather strips, probably belong here also.