I am currently in the process of making a scabbard for a recently acquired spatha, and I will need to suspend it from something. In order to come up with an appropriate belt or baldric based on finds from the Langobard necropolis at Nocera Umbra, I began researching the hardware associated with scabbards and sword suspension systems, which include small pyramidal fittings, often of bone. I carved myself one as an experiment, but was surprised to find how many of the graves from Nocera Umbra only had a single one, rather than the pairs I have seen used in reconstructions, so I decided to investigate this a bit further.

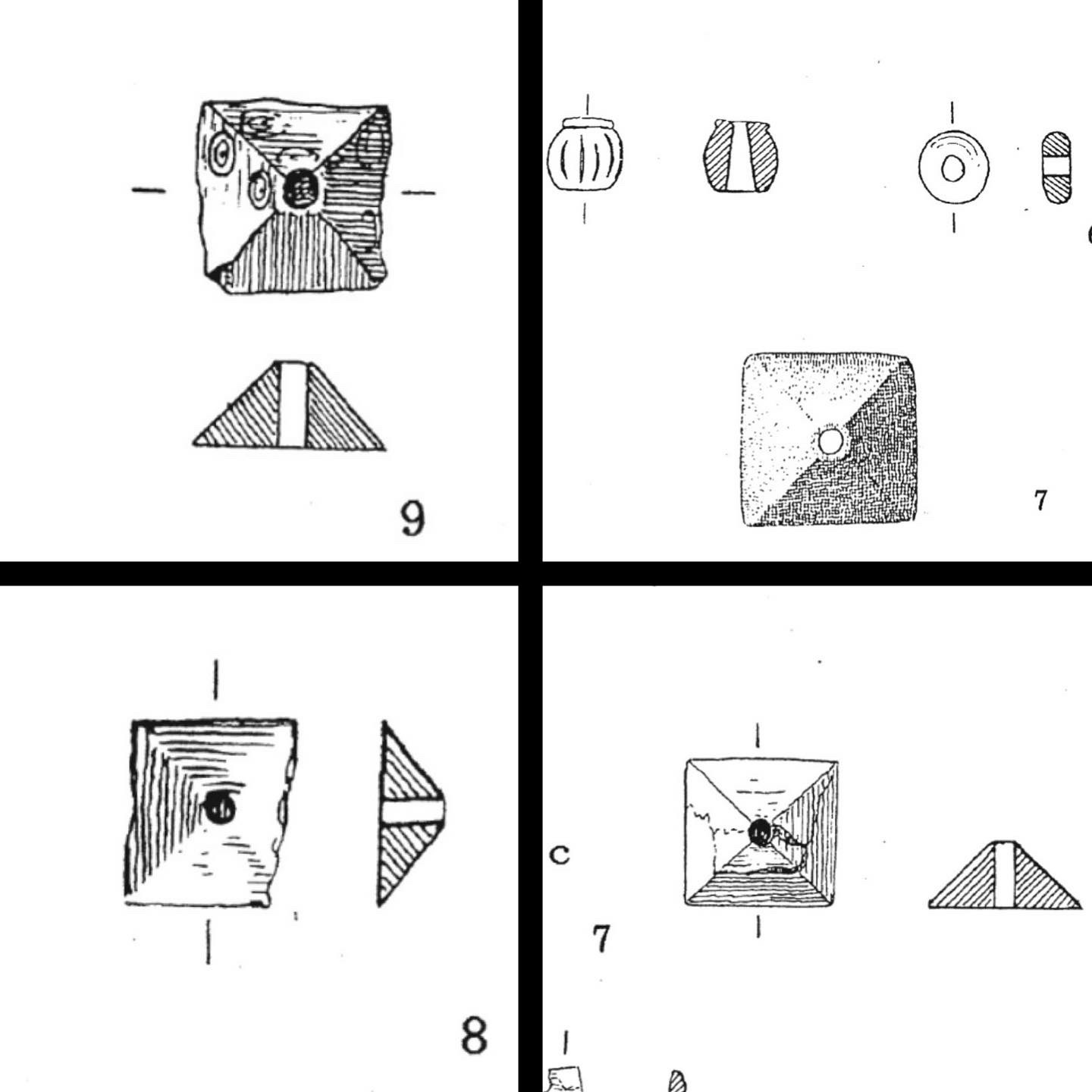

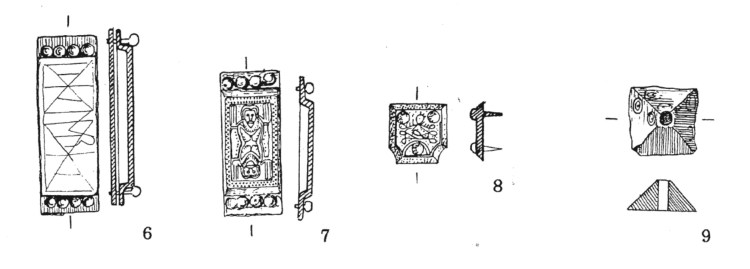

What are these pyramidal mounts? Odds are, you’ve seen one if you’ve browsed images of swords from Anglian/Saxon Britain and Frankish areas in the 6th/7th c. CE, where pairs of round or pyramid-shaped mounts are associated with spatha suspension and are generally interpreted as fasteners for the part of the strap that passes through the scabbard slide. The pyramidal ones are usually about 20mm square at the base and between 10 and 13 mm high. Many examples are of metal, including five pairs from the Staffordshire Hoard and others from Sutton Hoo. The bronze, gold, and silver examples usually have a bar on the underside for attachment (see below).

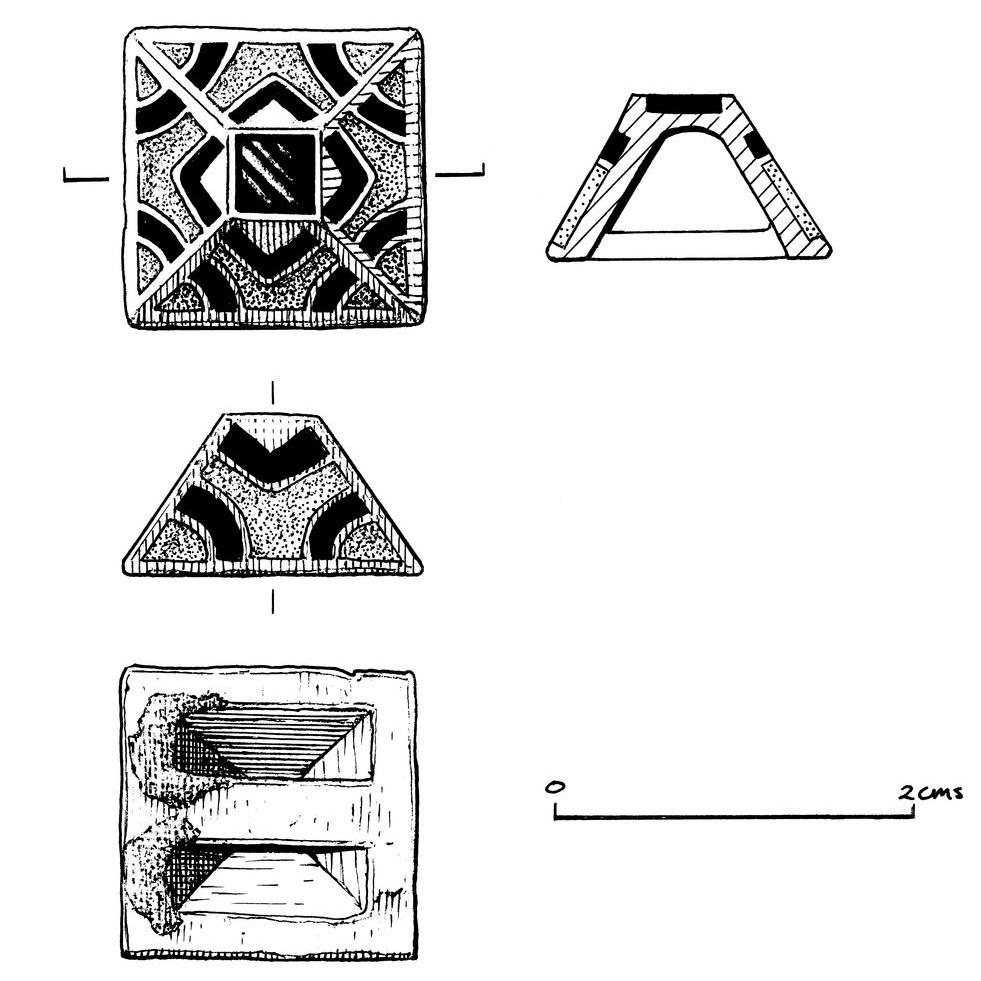

Examples found at Sutton Hoo, now in the collection of the British Museum. Images reproduced under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License.

Equivalents can be found in Vendel Period Scandinavia as well. The pressblech from the helmet in Vendel grave XIV shows two figures wearing swords suspended from baldrics. The two dots below the hilt of the swords appear to represent fittings on either side of the scabbard’s strap bridge.

In his study of Merovingian sword fittings from sites in modern-day Germany, Wilfried Menghin (1983) noted that in addition to the paired metal mounts, a second type of pyramidal mount with a slightly different shape was typically found alone. He also identified bone examples similar to the Nocera Umbra pyramids in several graves from Frankish-controlled areas. These include a paired set from Marktoberdorf (Grave 187) and several single examples as well. As these lack the bar found on the underside of the metal examples and simply have a central hole drilled through them, Menghin was unconvinced that they served the same function despite the similarity in size and shape and their association with swords and scabbards. Still, the finds of paired bone mounts alongside two-point suspension hardware suggest that even if this was a less-common practice and most served some other function as single items, they could also be used in the same way as their metal counterparts.

In Langobardic contexts in Italy, many examples of the pyramidal mounts are made of bone, including all the examples from the Nocera Umbra necropolis (Rupp, 2005). Like the Frankish bone examples Menghin documented, they have a central hole drilled from the apex through to the base (see image below).

Examples of bone pyramid mounts from Nocera Umbra at left; my reconstruction at right, based loosely on Grave 74.

Similar to their metal counterparts in neighboring regions, the examples from Nocera Umbra range from 18 to 23mm on each edge at the base and 12 to 15mm tall. The apex of the pyramid is flattened and the holes appear to be up to 3mm in diameter. Unlike the Scandinavian swords shown on the Vendel pressblech, no iconographic sources clearly depict scabbard furniture or suspension hardware in a Langobard context. But based on accompanying grave finds, the paired pyramidal mounts in Italy are typically associated with a “five piece” belt set, named for the number of principal hardware components, which appear similar to contemporary Merovingian sword belts. Reconstructions of this suspension system (see below) use the paired pyramid mounts on either side of the scabbard slide to secure a strap that attaches the spatha to the main belt or baldric, and in some versions a secondary strap runs from a lower attachment point to the rear of the main belt (Godino, 2016).

However, not all the Langobard graves that include pyramidal bone mounts also include the components of one of these more complex sword belts, and curiously, most of the spatha graves at Nocera Umbra with associated pyramid mounts only included a single one. Based on the catalog of the necropolis provided in the original 1918 publication and a subsequent catalog published in 2005, bone pyramids are associated with 12 burials that include spathas. Of these, only three actually contained a pair.

There are any number of possible reasons for this, including the following:

- Soil conditions cause one mount to decompose but not the other

- One of the two mounts was removed as part of a burial ritual

- Another (simpler?) suspension method existed that only required one mount

- Single pyramids were purely ornamental (a la “sword beads”) and were independent from a suspension belt or baldric

The first case seems extremely unlikely – the paired examples from Nocera Umbra are found very close to one another, and reconstructions of the sword belts place these mere centimeters apart on either side of the scabbard slide. The probability that accidental destruction or natural processes caused the loss of one mount but not both in over three-quarters of these burials seems extremely low. In some cases, Merovingian tombs include a mismatched set with a wooden pyramid alongside a metal one (Godino, 2016). While it is certainly possible that some of the single bone pyramids may have once been accompanied by a now-deteriorated wooden mate, this scenario would have to be present in the majority of the spatha graves for it to explain the excavation findings.

The second possibility, involving intentional removal of one of the two pyramids, is not implausible. Italian scholar Yuri Godino notes the textual evidence among the Langobards for a ritualized “breaking up” and dispersal of the deceased’s sword belt among his heirs. The redistribution of individual belt hardware elements is also supported by instances of burials where a single mount appears as an “intruder” that is not part of a set, possibly inherited from a relative (Godino, 2016). If we accept this explanation for all the missing pyramids at Nocera Umbra, I think it bears a review of the items found along with the mounts. Interestingly, the two mounts in Grave 132 are not identical in size (Pasqui & Paribeni, 1918); while this may simply be a case in which one pyramid was lost and replaced during the owner’s lifetime (in this case replaced in kind, not with wood), this could also support a hypothesis that these mounts were removed as part of a ritual deposition and incorporated into a relative’s belt set.

The original publication from 1918 lists no additional buckles, plates, or other belt hardware accompanying the single bone pyramids in two out of thirteen graves (Graves 111b and 115). If a belt or baldric was broken up and redistributed among the deceased’s heirs, the pyramid may have been left behind as synecdoche to represent the rest of the belt, although the excavation report does not provide me with any clues as to how it might have related to the scabbard at the time of deposition – was the pyramid placed back in the grave atop the spatha, or was the fastening system made in such a way that it was still attached to a strap on the scabbard after the rest of the belt was removed? More on this in a moment…

Of the three graves that retain paired mounts (Graves 98, 111, and 132), each one also contained belt hardware with four or five surviving components – a buckle, counterplate, and additional square and rhomboid plates that can be interpreted as parts of the “five-piece” belt set. One of the single-pyramid graves (Grave 156), included a buckle, strap end, rhomboid plate, square plate, and strap slide that may be part of a similar suspension belt, and another contained a buckle with a triangular plate, counterplate, strap end, and rectangular plate associated with a sword belt (Grave 106). In these cases, most or all of the richly decorated belt hardware remained in the grave; unless both are cases where a wood pyramid decayed while a bone one survived, either the belt was left intact and only ever had a single pyramid, or the removal of one of the two pyramids may have been sufficient to “complete” the ritual of breaking the belt apart. This assumes, however, that the symbolic breaking of the belt was more important than the actual redistribution of the hardware involved – an assumption for which I can find no evidence.

Graves 20 and 137 included buckles with a large number of matching strap end fittings that appear to be part of a different belt style known as the “multiple belt,” comprised of a main waist belt with many short, perpendicular dangling straps, each fitted with a decorative metal tip. In Langobard graves, the remains of such belts are generally found on the waist of the deceased, while the spatha is typically deposited to one side (Godino, 2016). Although these belts may have held up a seax, they do not appear to be related to sword suspension. In Graves 20 and 137, the belt components were found on the deceased’s pelvis/abdomen, while the spatha was laid to the side. No fittings are noted with the spatha except for the single pyramid found on the tang in Grave 137. In Grave 20, the scabbard included a pair of bone splines just below the hilt, along with a small silver buckle and single bone pyramid (Pasqui & Paribeni, 1918).

The remaining three examples were found in graves with some sort of buckle and/or strap fitting, but without a larger belt set. In Grave 163, a simple elliptical buckle was found resting on the spatha blade. Although the original 1918 publication does not mention a bone pyramid, one is included with the grave assemblage in the collection of the museum and is noted in the 2005 publication; however, its orignal position in the grave is unknown. In Grave 139, a pyramid was found on the spatha blade and a strap end, buckle, and two glass beads were found nearby between the thorax and the deceased’s right elbow. Grave 74 included a single pyramid and the associated belt components consist of a large elliptical iron buckle, two “box mounts” and a Y-shaped plate (see image below).

It is this last assemblage that has an interesting contemporary parallel from Pannonia, the area where the Langobards had resided immediately prior to their arrival on the Italian Peninsula in the second half of the 6th century. This grave, likely belonging to a Gepid warrior, is located in Tiszagyenda, Hungary, and is dated to c.600-610 CE. Its contents show clear Langobardic and Frankish influences (see Kocsis and Molnar, 2021) and also provide support for the third possibility mentioned earlier—that another suspension method requiring only one pyramidal mount coexisted with the paired mount/”five-piece” belt option. In this burial, a single bronze pyramid was found atop the scabbard, embedded in the remains of an organic slider and oriented in such a way that the authors of an article in a Hungarian journal believe that it was never part of a pair. They propose that the spatha hung from a baldric, and the pyramid was attached directly atop the scabbard slide, ostensibly to secure the strap to the slider for this single-point suspension. Like Nocera Umbra Grave 74, the sword belt included a set of box mounts (two comparably-sized rectangular ones but also two smaller square ones), and the Y-shaped plates are also similar in form and dimension to the one in Grave 74. Authors Kocsis and Molnar propose that these served as strap width reducers, joining the wider main portion of the baldric to a narrower section that wrapped around the scabbard (see diagram below).

Altogether, the assemblage in the Tiszagyenda grave is strikingly similar to that of Nocera Umbra 74, and the specificity of the bronze pyramid’s position at Tiszagyenda provides compelling evidence for a similar function for the single bone pyramid in Nocera Umbra 74. The use of a single pyramid mounted directly on the scabbard slide would also explain the absence of any other sword suspension hardware in Graves 20, 111b, and 115, if a richly decorated belt or baldric was removed entirely and either given to an heir or broken up for distribution among multiple heirs. In Graves 163 and 139, the single buckles may be the only metal fitting for a simpler baldric, or other plaques may have been removed prior to deposition.

And of course, the position of the mount at Tiszagyenda also raises the possibility that a single pyramid may have been attached directly to the scabbard slide without serving any function beyond ornamentation. This would also provide a satisfactory explanation for most, if not all, of the Nocera Umbra graves with only one pyramid. Although this leaves me wondering why nearly all of the Nocera Umbra examples were plain – an undecorated object made of a common material hardly seems like the sort of thing that would add prestige to a status symbol like a spatha, although it would be interesting to find out whether any were once painted, perhaps in imitation of a gold cloisonné version?

In summary, the available evidence is not sufficient to say with any certainty what role funerary rites may have played in the presence or absence of specific components of a spatha suspension belt or baldric. However, taken all together, the Nocera Umbra finds suggest that there were multiple modes of spatha suspension, and that pyramidal mounts were involved with both the “five piece,” two-point method as well as a one-point method involving a simpler baldric. The Tiszagyenda example supports this latter interpretation and its association with single bone pyramids, and gives us a rare example of a pyramid mount found in what appears to be its original location, clearly affixed to the scabbard slide. Whether the pyramidal mount was integral to the suspension system or served some ancillary (or purely decorative) purpose remains to be seen, but I plan to experiment with the pyramidal mount I made to see how this works in practice; look for a future blog post in the next month or so.

Sources:

Godino, Yuri. 2016. Menswear of the Lombards: Reflections in the light of archeology, iconography and written sources. Rimini: Bookstones Press.

Kocsis, L., & Molnár, E. (2021). A 6th–7th century solitary burial of a warrior with his horse at Tiszagyenda, Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 72(1), 137-192.

Pasqui, A., & Paribeni, R (1918). La necropoli barbarica di Nocera Umbra, “Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei”, XXV, 137-346.)

Rupp, Cornelia. 2005. Das langobardische Gräberfeld von Nocera Umbra. Borgo San Lorenzo (Fi): All’insegna del giglio.